RWYM

WHAT IS DRESSAGE?

A PERSONAL VIEW BY MARY WANLESS

Dressage is the ‘systematic training of the horse….’ The familiarity of this definition tends to blind us to the fact that it expresses a lofty and theoretical ideal. It contains a tacit assumption which I think idemeans our sport, even though it presents a misguided attempt to idealise it. For the text book definition of dressage presupposes that riders who pursue its hallowed path will have the skills needed to follow the ideal progression of training. The definition ignores what I consider to be the ‘grist to the mill’ of dressage – its challenges, its substance, its light and its darkness – for it assumes that the obstacles faced by the aspiring rider have already been overcome. We remain much closer to real life if we define dressage training as the process through which riders inter-act with their horses from moment to moment, and learn the skills to do so in more refined and effective ways.

We are so besotted with the idea of training horses that we pay the merest lip service to the process through which riders learn their skills. Perhaps this is because good riders make it look so easy, and make the horse’s correct response seems so natural and inevitable. The difficulties and evasions which beset less experienced riders just do not materialise for them. But we all know that frayed tempers and push-pull tactics lie just around the corner for many. So what percentage of riders have the skills to systematically train their horses according to the text book ideal, and what does dressage become for the vast majority of riders who do not? More importantly, what does it become for their horses?

For all but the most talented riders, becoming skilful demands so much learning that we are challenged on every front. As well as gaining intricate physical skills, we have to gain a subtlety of perception that can match the perceptions of our horses: in other words, we have to learn to read them in the way that they so instinctively read us. This gives them the intimate knowledge of our physical, mental and emotional weaknesses. As well as arranging their bodies according to our asymmetry, our floppyness, or our bumpyness, they also sense our committment level, and our bottom line. This knowledge is power – espressed in every equine form from being outrageously lazy to running rings around us. All too easily we become the victims of horses who can out-manoever us (the partners they probably regard – on a good day – as ‘muggles’).

The emotional responses which arise in us when the horse thwarts our intentions frequently turn riding into a power struggle, and this brings another dimension into our learning. If we are impatient, we have to learn to become patient. If we lack authority, our horses will demand that we develop it. If we lack sensitivity, we are challenged to develop that too – and then to demonstrate these apparently opposing qualities in one body-mind. This is asking a tremendous amount of us. For to be good riders we have to become what we are not – as does the horse. The horse with run-away tendencies has to learn to contain himself, and to wait for the rider. The lazy horse has to learn to committ his energy to the task. In our work with him, we challenge more than his balance and his asymmetry. We challenge him to develop his ‘horseonallity’ – hopefully in ways which make him more powerful, beautiful, willing, trusting, and whole, and not in ways that force him to become more desperate and devious.

Only a small percentage of riders appreciate the damage inflicted on the horse when an ambitious rider throws her weight around, and how the escape routes choosen by the horse will turn him into a ‘head-case’ of various descriptions. Many horses, for instance, ‘space out’, absenting themselves psychically from their inter-action with the rider. To the less experienced, it can appear that nothing is wrong, for there is unlikely to be the hysteria of the panicing horse, or the overt signs of rebellion shown by the horse who has thrown in the towel. But in a huge number of cases, all is not well with the horses we had expected to be our partners.

But when dressage training does go well, it encompasses so much than mere gynmastics. The learning process shared by horse and rider encapsulates so many dimensions of their being that it has physical, mental, emotional and even spiritual elements. It is like peeling away the layers of an onion – except that this onion has no middle, and every time you start to think that you have reached it, a new layer of subtlety will become apparent to you. You may dream of arriving, but this is a journey in which there has to be joy in travelling, otherwise you will be miserable 95% of the time, and will inflict this misery on your horse. You and he are both ‘works in progress’ as you travel along a path of personal (and ‘horseonal’) development that is probably unsurpassed within the framework of a martial art’s training or Bhuddism. The Master, or teacher, is the horse. We riders are the pupils.

This turns established thinking on its head, for it is humans, surely, whose position as superiour species designates them as teacher? There is a comon myth that riders, in their infinite wisdom, get to ‘teach the horse to come on the bit’, but the riders who sit up there and make it look so easy have overcome this illusion of superiourity. They know (in the words of Egon Von Neindorff) that ‘the horse already knows how to be a horse, and therefore the problems of equitation are entirely those of the rider’. The riders who sit so still yet look so powerful have achieved their skill level by adopting an ‘I-Thou’ relationship of equality with their horses. They have the humility to listen to the horse, and to learn from him.

In good work, horse and rider are part of a feedback system. The ‘game’ of dressage riding is a ‘game’ of inter-action in which I as rider feel the horse change (say he falls on one shoulder) and I counter his move by straightenning him. He responds to my move, so I sit still. The next time I sense that he is about to fall on his shoulder, I counter his move before it even happens. I have had a conversation with the horse which – if I was subtle enough – will not be noticed by an observer. If my move works well, I sit still again. This stillness, in which I do not intervene, becomes the horse’s reward. I may then feel him about to slow down, so I counter that move. Perhaps I over-correct, making him speed up, and if so, I let him drop back a little. Just as he is about to slow down too much I send him forward, hopefully with so much subtlely that you as observer never see this conversation happen.

When the horse and the rider are less highly trained and/or beginning something new, the conversation between them becomes more obvious. Instead of saying ‘I get it’

and responding to the rider’s move, the horse may reply ‘But this doesn’t make sense in ‘horse’’. He then continues in his own sweet (evasive) way, leaving the rider either searching for a way in which her move will make sense or ‘shouting louder at the natives’. Once the rider’s side of the conversation degenerates into push-pull (the loudest of shouts, often amplified by draw reins and other gadgets), you can be sure that she has run out of tools in her riding ‘tool kit’.

When riders attempt to ‘teach’ the horse to ‘come on the bit’ they normally assume that they are appealing to his rational mind. Many riders think that horses learn as humans learn. (‘She just kicked three times with her left leg and twiddled on the right rein. Now what’s that supposed to mean? I seem to have forgotten…’) But this is not so. Underlying all our attempts to ‘teach’ the horse lies a system of reflex inter-actions which cannot not happen, and these determine the outcome of our efforts. The bottom line is that placing your weight on the back of A. N. Other green horse will cause him to hollow it. He will also retract his rib cage away from your legs, and may come ‘above the bit’, retracting his mouth from your hand. He will probably reduce the depth of his breathing. I call these responses the ‘cramping reflexes’. They lead to stilted movement, and a jarring ride. If you then ignore them as you attempt to ‘teach’ (or force) your horse to make his nose vertical, you will – at best – produce a horse with a hollow back and a vertical nose. This is a common sight, but not a pretty one, for it makes the horse look as if his head is too big, and his neck too short. At worst, the horse will inform you in no uncertain terms that his body will not be cramped into this contortion.

You could then be tempted to decide that your horse is ‘stupid’ ‘evasive’ or ‘not listening’, and you may even believe that he ‘ought to know better’. (Some riders even act as if their horses have stood in their stables for the last twenty-three hours thinking to themselves ‘How can I make her really mad tomorrow?’) Horse are not blank slates, and they are not totally innocent; but neither are they ‘out to get us’ in the way that our devious preditory mind imagines. It’s just that their physique, history, and temperament combine together to set the rider a problem to solve, and the only relevant question is whether she has the tools in her tool kit to solve that problem. But fuelled by ignorance and ambition, she may instead dig herself in more deeply, inflicting physical and psychological damage on her horse – who will confirm her worst opinions of him by becoming more evasive.

The primary challenge of dressage riding is to learn how to sit so well that your horse natually, willingly, comes into ‘the seeking reflexes’. As he begins to seek contact with your seat, leg and hand his back lifts, his rib cage fills out, and his breathing deepens and becomes regular. His neck lengthens, reaching out of the wither, and his head no longer looks too big. Any horse who shows the biomechanics of correct movement in his body will begin to look like the archetypal dressage horse, whatever his make and shape, and however much you paid for him. The trick to dressage riding lies in knowing the rules of the rider/horse interaction – the rules of cause and effect which form the science that underlies the art. You then obey those rules. You search (aided by your teacher) for your remaining ‘blind-spots’, discovering the aspects of your sitting which perpetuate the cramping reflexes, and collude with your horse’s evasive patterns. You also seek to unravel the asymmetry that you are imposing upon him. And you listen, moment by moment, for your horse’s response to each of your interventions.

Good training renders the horse more willing to play the game by our rules, to respect the framework that is created by our body, and to nudge it out of place rather than bashing it out of place. (After all, their 1200 lbs plus may pitted against only 120 lbs.) This means that the art of riding lies in making the horse easy to ride, and as a consequence the learning rider has the most enormous mountain to climb. (I consider this one of the most devastating truths of riding). But life is not even this simple, for as we riders unravel the ‘onion’ of riding, our horses unravel it too, and they keep demanding that we play the inter-action game at more and more refined levels.

Horses have an uncanny knack of finding neat little evasions which capitalise on our weaknesses. These may involve a crookedness, a lack of impulsion, or a ducking behind the bit, and they can be so subtle and clever that they are just as difficult to deal with as the cruder evasions of the green horse. The horse is like a tennis partner who exploits the vulnerability of our backhand, and some make a career out of countering our every move and ‘playing tennis’ with us! Others employ much more subtle tactics, and they ease our framework out of place without us even knowing that they did it. Only the very skilful rider who leaves few (if any) loopholes can train correct patterns in her horses. Only a skilful and wise rider respects and preserves his generosity so that he remains willing to exert himself, and to work within those patterns.

The science of cybernetics informs us that within any system of human beings or machines (and I think we can safely include the human-horse system in this) the element within the system which has the greatest number of choices within its behaviour will become the controlling element. This, in effect, makes it the most intelligent element in the system. When kids have more behavioural choices than their parents they out-wit them, and when horses have more choices than their riders they too are out-played.

Unfortunately, we are ‘wired’ in ways which predispose us to repeatedly do the same thing in the same way, so ‘shouting louder at the natives’ comes naturally until we develop more choices in our behaviour. When we learn riding skills we are, in effect, becoming ‘dextrous’ with the pelvic area, learning the moves that can counter the horse’s moves (although we will, paradoxically, appear to sit still as we do them). We need to gain a greater repatoire of neurological choices, but we are working with a part of the body which is not well represented in the cortex.

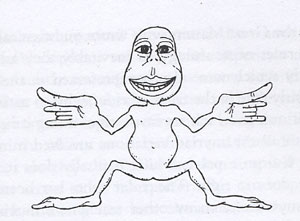

The homonculus (Fig 1) shows the person your brain thinks you are. Your enormous thumbs, and your big hands, mouth and eyes, are a testament to the vast number of neurological messages that pass between them and your brain. Your tiny pelvis is a testament to how few messages are relayed to and from that area. It is no wonder that you will instinctively attempt to solve the problems of riding with your hands, and no wonder that it takes a long time to gain the awareness, the subtlety and the ‘wiring’ to choose to act with your pelvis instead.

The emphasis on the rider’s hand and lower leg in most riding texts can again be attributed to the homonculus. Despite the enormity of their skill, the old masters had much greater awareness of what they were doing with their extremities than of how they organised their centre. So they missed telling us about the most important ways in which we can communicate with our horses. In fact, they gave us the icing, but not the cake. They also lacked the knowledge to tell us that riding is a dynamic isometric skill, based on the ability to stabilise the body on top of a moving medium. Stability is required before the rider can hope to have influence – otherwise how is the horse to know which wobbles and jerks are supposed to mean anything and which are not? The ‘noise to signal’ ratio is rarely in his favour: we have to cut out the noise in order to send or receive meaningful messages.

Biomechanically, riding poses similar issues to skiing, snow boarding, surfing and wind surfing. None of these are solved simply by relaxing – although I am not suggesting that it pays to be ‘uptight’. Neither can they be solved by putting your hands and legs in certain places. Stability is gained by pitting opposing muscle groups against eachother, and you use your muscles similarly to the way you would if you were to push against a heavy wardrobe that you cannot move. A very small percentage of riders (the ones that we call ‘talented’) discover this isometric muscle use. However the vast majority of riders remain in the ‘default setting’, which I call water-skiing, since they are towed along by the horse who plays the part of the motor-boat. If you are not going to be towed, and not going to be dependent on a backward traction on the rein, you have to match the forces that the horse’s movement exerts on your body. In order not to pull back, you make a push forward within your body (almost like pushing the wardrobe whilst remaining in a riding alignment). Then you can ride along saying, ‘Look, no hands.’. Your horse will then become far more malleable, for finally you are saying it in ‘horse’.

The inter-action game can now be played in a far more effective and subtle way. In fact, the skilled riders who write the books play it so unconsciously that they rarely make it explicit. They tell us about the aids for certain movements, but not about a moment-to-moment inter-action in which horse and rider respond to each other with minute subtlety. We hear much more about what trainer Charles De Kunffy calls the rider’s ‘second tool kit’ which is the school movements and the gymnastic challenges that they set. The largely unacknowledged side of riding is the rider’s ‘first tool kit’, which is her body, and her ability to organise the horse simply through the way that she sits. This, I believe, is the most important element in riding.

Think of the rider who has bought herself a trained horse, probably for a vast sum of money. If the rider/horse relationship mirrors a couple’s dance form – say ballroom, jazz dance, or rock and roll – then the rider is analogous to the man, and the horse plays the role of the woman. If you have ever danced with a good male partner you will know that you do not have to know the steps – it’s as if you are danced, and you can probably testify that this is a wonderful feeling. But suppose that you then change partners, and that this man is not such a good dancer. Suddenly he is pulling and you are pushing, and in a flurry of disorganised angst you find yourself thinking ‘But I don’t know the steps…’.

If you were a horse that your new partner had just bought he might even think ‘But I paid all that money for this horse, and I thought he’d been trained! He ought to know better than this…’ But the horse has no more chance of ‘dancing’ with his new rider in the way he danced with his old one than you have of dancing with your new partner in the way you danced with your old one. The idea that the horse ‘ought to know better’ represents a total misunderstanding of what it means to ‘dance’ with a horse. A trained horse is not a fixed entity carved in stone. It will never be a case of pressing button B and waiting for the correct response. He will make you play the inter-action game, and when you cannot play to his standards he will run circles around you. For he will have many more behavioural choices than you have.

Yet the myth of the trained horse persists – and riders who earn their living by producing such horses have a vested interest in preserving it. But I heard it contradicted recently by a world-renowned trainer, who stated that when you observe a rider/horse combination, 95% of what you see is attributable to the rider. I may be one of the few people to agree with him, for on the other end of the spectrum, the more commonly held belief is expressed in a story I read recently. It described a man who had begun event riding after a lifetime of hunting and point to pointing. This required his first introduction to dressage, and he described his relief in discovering that apart from the ten marks attributed to his riding, only the horse was scored. His conclusion was that it really did not matter how he achieved a correct result… He probably thinks, as I did many years ago, that one circle is much like another, and that he knows how to ride them. He has negated the inter-action game, the moment-by-moment conversation that takes place between rider and horse. But so has our standard definition of dressage. So have the dressage judges who only look at the horse, and the trainers who prescribe school movements regardless of the rider’s skills. These parties have also negated the even more hidden aspect of riding – the way that the rider’s ‘first tool kit’ influences the horse’s carriage, and the devastating effect on the horse of a high ‘noise to signal’ ratio. Our traditional viewpoint has encouraged us to ignore the cake and see only the icing.

You can play the inter-action game with any horse. If you want to do so in front of a dressage judge, you will score far better if you have a horse with presence and good paces. You also need a horse who is physically robust enough to work ‘through’, and not one of the ‘walking wounded’ (not actually limping, but compromised by pain somewhere in his body). To score well when you play the game, you need slick and effective corrections that you can pull out of your ‘tool kit’ at a moment’s notice. Few riders have. Those in the process of developing this ability may have to ‘grope’ around for the right response – since it will (as a rule of thumb) take 10,000 repetitions of that new co-ordination before it becomes their automatic choice.

The homonculus (Fig 1) shows the person your brain thinks you are. Your enormous thumbs, and your big hands, mouth and eyes, are a testament to the vast number of neurological messages that pass between them and your brain. Your tiny pelvis is a testament to how few messages are relayed to and from that area. It is no wonder that you will instinctively attempt to solve the problems of riding with your hands, and no wonder that it takes a long time to gain the awareness, the subtlety and the ‘wiring’ to choose to act with your pelvis instead.

The emphasis on the rider’s hand and lower leg in most riding texts can again be attributed to the homonculus. Despite the enormity of their skill, the old masters had much greater awareness of what they were doing with their extremities than of how they organised their centre. So they missed telling us about the most important ways in which we can communicate with our horses. In fact, they gave us the icing, but not the cake. They also lacked the knowledge to tell us that riding is a dynamic isometric skill, based on the ability to stabilise the body on top of a moving medium. Stability is required before the rider can hope to have influence – otherwise how is the horse to know which wobbles and jerks are supposed to mean anything and which are not? The ‘noise to signal’ ratio is rarely in his favour: we have to cut out the noise in order to send or receive meaningful messages.

Biomechanically, riding poses similar issues to skiing, snow boarding, surfing and wind surfing. None of these are solved simply by relaxing – although I am not suggesting that it pays to be ‘uptight’. Neither can they be solved by putting your hands and legs in certain places. Stability is gained by pitting opposing muscle groups against eachother, and you use your muscles similarly to the way you would if you were to push against a heavy wardrobe that you cannot move. A very small percentage of riders (the ones that we call ‘talented’) discover this isometric muscle use. However the vast majority of riders remain in the ‘default setting’, which I call water-skiing, since they are towed along by the horse who plays the part of the motor-boat. If you are not going to be towed, and not going to be dependent on a backward traction on the rein, you have to match the forces that the horse’s movement exerts on your body. In order not to pull back, you make a push forward within your body (almost like pushing the wardrobe whilst remaining in a riding alignment). Then you can ride along saying, ‘Look, no hands.’. Your horse will then become far more malleable, for finally you are saying it in ‘horse’.

The inter-action game can now be played in a far more effective and subtle way. In fact, the skilled riders who write the books play it so unconsciously that they rarely make it explicit. They tell us about the aids for certain movements, but not about a moment-to-moment inter-action in which horse and rider respond to each other with minute subtlety. We hear much more about what trainer Charles De Kunffy calls the rider’s ‘second tool kit’ which is the school movements and the gymnastic challenges that they set. The largely unacknowledged side of riding is the rider’s ‘first tool kit’, which is her body, and her ability to organise the horse simply through the way that she sits. This, I believe, is the most important element in riding.

Think of the rider who has bought herself a trained horse, probably for a vast sum of money. If the rider/horse relationship mirrors a couple’s dance form – say ballroom, jazz dance, or rock and roll – then the rider is analogous to the man, and the horse plays the role of the woman. If you have ever danced with a good male partner you will know that you do not have to know the steps – it’s as if you are danced, and you can probably testify that this is a wonderful feeling. But suppose that you then change partners, and that this man is not such a good dancer. Suddenly he is pulling and you are pushing, and in a flurry of disorganised angst you find yourself thinking ‘But I don’t know the steps…’.

If you were a horse that your new partner had just bought he might even think ‘But I paid all that money for this horse, and I thought he’d been trained! He ought to know better than this…’ But the horse has no more chance of ‘dancing’ with his new rider in the way he danced with his old one than you have of dancing with your new partner in the way you danced with your old one. The idea that the horse ‘ought to know better’ represents a total misunderstanding of what it means to ‘dance’ with a horse. A trained horse is not a fixed entity carved in stone. It will never be a case of pressing button B and waiting for the correct response. He will make you play the inter-action game, and when you cannot play to his standards he will run circles around you. For he will have many more behavioural choices than you have.

Yet the myth of the trained horse persists – and riders who earn their living by producing such horses have a vested interest in preserving it. But I heard it contradicted recently by a world-renowned trainer, who stated that when you observe a rider/horse combination, 95% of what you see is attributable to the rider. I may be one of the few people to agree with him, for on the other end of the spectrum, the more commonly held belief is expressed in a story I read recently. It described a man who had begun event riding after a lifetime of hunting and point to pointing. This required his first introduction to dressage, and he described his relief in discovering that apart from the ten marks attributed to his riding, only the horse was scored. His conclusion was that it really did not matter how he achieved a correct result… He probably thinks, as I did many years ago, that one circle is much like another, and that he knows how to ride them. He has negated the inter-action game, the moment-by-moment conversation that takes place between rider and horse. But so has our standard definition of dressage. So have the dressage judges who only look at the horse, and the trainers who prescribe school movements regardless of the rider’s skills. These parties have also negated the even more hidden aspect of riding – the way that the rider’s ‘first tool kit’ influences the horse’s carriage, and the devastating effect on the horse of a high ‘noise to signal’ ratio. Our traditional viewpoint has encouraged us to ignore the cake and see only the icing.

You can play the inter-action game with any horse. If you want to do so in front of a dressage judge, you will score far better if you have a horse with presence and good paces. You also need a horse who is physically robust enough to work ‘through’, and not one of the ‘walking wounded’ (not actually limping, but compromised by pain somewhere in his body). To score well when you play the game, you need slick and effective corrections that you can pull out of your ‘tool kit’ at a moment’s notice. Few riders have. Those in the process of developing this ability may have to ‘grope’ around for the right response – since it will (as a rule of thumb) take 10,000 repetitions of that new co-ordination before it becomes their automatic choice.

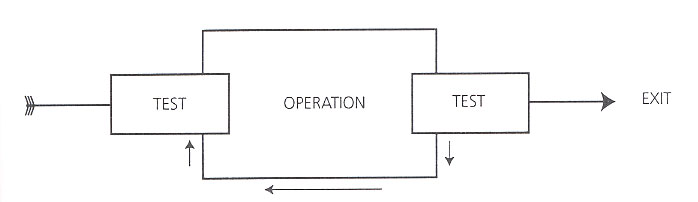

Whilst riders ‘grope’ like this they have to pay attention internally, and will not make a good job of looking up, knowing where they are, knowing where they are going, and riding the test in a strategic point-gaining way. To use computer language they are ‘stuck in the TOTE’, where TOTE stands for Test, Operation, Test, Exit (See Fig 2). The first Test asks, ‘Does the feeling I am getting match the feeling I really want to get?’. If the answer is ‘yes’, then the rider has nothing to do. If it is ‘no’ then she has to perform an Operation before she asks herself the same question. If the answer is now ‘yes’ (if her ‘operation’ was successful) she gets to exit the TOTE, and again she has nothing to do – except ride the test. If the answer is ‘no’ she gets to grope some more until she does come up with a successful Operation.

The good rider (and in particular the good competition rider) spends far more time out of the TOTE than in it. Riders who are learning to produce successful operations spend far more time inside the TOTE than out of it; but this is how learning happens, and it is far more productive, and far more fun, than ‘shouting louder at the natives’. Learning also involves the development of increasingly stringent ‘reference feelings’, and the further a rider travels into the ‘onion’ of riding, the more she develops a ‘right’ that becomes right enough to impress both humans and horses. In high-class company, a woolly sense of ‘right’ will not score well.

On the way to this lie many blind alleys, and many cycles of 10,000 repetitions. For if you are a disorganised rider, your horse will succeed in disorganising you more, and only when you are a highly organised rider will you be able to organise the disorganised horse. You will then earn his respect, and perhaps even his love. But do not expect that the game will then be over, for our horses cannot not play it. Whenever you absent yourself mentally, for instance, your horse will find the loophole that you have just created. And despite all our illusions of superiority, this leads us to the embarrassing conclusion that our horses know more about what goes on inside our heads than we do!

Learn well, O human, if you wish to become as wise – and as canny – as your horse. Learn well, too, if you wish to live the love that lies in your heart, to transcend the crude inter-action that so many perceive as a battle, and to say it in the resistance-free language of ‘horse’. If you do, you will gain so much, and riding skills are only part of that prize.

Copyright Mary Wanless June 2001

Whilst riders ‘grope’ like this they have to pay attention internally, and will not make a good job of looking up, knowing where they are, knowing where they are going, and riding the test in a strategic point-gaining way. To use computer language they are ‘stuck in the TOTE’, where TOTE stands for Test, Operation, Test, Exit (See Fig 2). The first Test asks, ‘Does the feeling I am getting match the feeling I really want to get?’. If the answer is ‘yes’, then the rider has nothing to do. If it is ‘no’ then she has to perform an Operation before she asks herself the same question. If the answer is now ‘yes’ (if her ‘operation’ was successful) she gets to exit the TOTE, and again she has nothing to do – except ride the test. If the answer is ‘no’ she gets to grope some more until she does come up with a successful Operation.

The good rider (and in particular the good competition rider) spends far more time out of the TOTE than in it. Riders who are learning to produce successful operations spend far more time inside the TOTE than out of it; but this is how learning happens, and it is far more productive, and far more fun, than ‘shouting louder at the natives’. Learning also involves the development of increasingly stringent ‘reference feelings’, and the further a rider travels into the ‘onion’ of riding, the more she develops a ‘right’ that becomes right enough to impress both humans and horses. In high-class company, a woolly sense of ‘right’ will not score well.

On the way to this lie many blind alleys, and many cycles of 10,000 repetitions. For if you are a disorganised rider, your horse will succeed in disorganising you more, and only when you are a highly organised rider will you be able to organise the disorganised horse. You will then earn his respect, and perhaps even his love. But do not expect that the game will then be over, for our horses cannot not play it. Whenever you absent yourself mentally, for instance, your horse will find the loophole that you have just created. And despite all our illusions of superiority, this leads us to the embarrassing conclusion that our horses know more about what goes on inside our heads than we do!

Learn well, O human, if you wish to become as wise – and as canny – as your horse. Learn well, too, if you wish to live the love that lies in your heart, to transcend the crude inter-action that so many perceive as a battle, and to say it in the resistance-free language of ‘horse’. If you do, you will gain so much, and riding skills are only part of that prize.

Copyright Mary Wanless June 2001