RWYM

ARTICLE 11

This rider has owned her horse for nearly three years. She states in her letter to me that ‘My mare was very green when I bought her as a six year old. Whilst her schooling has improved tremendously I have never been able to achieve true connection from leg to hand and forward into a contact.’. The rider passed her BHS stage three examination before she bought her horse, but I presume that she is not working professionally with horses, since she also states ‘Due to my job moving several times I have had several different instructors. While they were all immensely talented instructors they have all had slightly different techniques for teaching a horse to go forwards into a contact. As a result both Sadie and I are very confused! I understand the importance of a good position and the fact that the power must come from behind into a contact, but that this contact should be light and the horse should not be pulled in! I can get a round outline but this involves some fiddling of the reins or a very strong contact that I know I should not have to use. When she does go round she stops going forward, probably as a result of the roundness being hand orientated. She has also started to resist the forward aid, swishing her tail or bucking (she has had teeth, back, saddle etc. checked). I would like to know how I can train my horse to go forward into a light contact while maintaining power from behind and how I can improve my position to achieve this. Three years ago I really thought I knew the answer; however I now find myself completely stumped!’.

This rider has owned her horse for nearly three years. She states in her letter to me that ‘My mare was very green when I bought her as a six year old. Whilst her schooling has improved tremendously I have never been able to achieve true connection from leg to hand and forward into a contact.’. The rider passed her BHS stage three examination before she bought her horse, but I presume that she is not working professionally with horses, since she also states ‘Due to my job moving several times I have had several different instructors. While they were all immensely talented instructors they have all had slightly different techniques for teaching a horse to go forwards into a contact. As a result both Sadie and I are very confused! I understand the importance of a good position and the fact that the power must come from behind into a contact, but that this contact should be light and the horse should not be pulled in! I can get a round outline but this involves some fiddling of the reins or a very strong contact that I know I should not have to use. When she does go round she stops going forward, probably as a result of the roundness being hand orientated. She has also started to resist the forward aid, swishing her tail or bucking (she has had teeth, back, saddle etc. checked). I would like to know how I can train my horse to go forward into a light contact while maintaining power from behind and how I can improve my position to achieve this. Three years ago I really thought I knew the answer; however I now find myself completely stumped!’.

I too have memories of the time when, as a newly qualified BHSAI, I thought I knew all about riding! How embarrassing it feels to admit that now, and I am never sure how much this results from the folly of youth, or from a training which all too commonly instils arrogance but does not deliver the goods. This rider can talk the talk – albeit in rather vague, generalised terms – but she is discovering that she cannot ride that talk. In this, she is one of many. But she is one of the few to realise that what she is actually doing through her riding is eroding her mare’s generosity and training evasive patterns. The good news is that this awful, heart-rending realisation can catalyse tremendous learning – just as it did for me twenty years ago.

Our rider has fallen into the enormous hole that lies between experience, and the language which is used to describe that experience. Her teachers told her that ‘the power should come from behind into a light contact’. This gave her a wonderful ideal, but it told her nothing about the rider biomechanics that would enable her to achieve it! Somehow, just knowing the theory was supposed to enable her to do it… yet millions of riders prove every day that theory and practice are two completely different realms.

The discrepancy arises because of the different processing modes of the left and right brain hemispheres: the left brain hears the words or reads the books, and thinks that it knows all about riding. But it is the right brain, which has little or no access to language, which controls the body and does the job. Because of this, good riders really struggle to describe their skills in words, in the same way that they (or you) would struggle to explain the taste of strawberry jam. Your senses can distinguish strawberry from raspberry, but how would you explain that difference? Faced with the equivalent problem, riders effectively say ‘Well, strawberry jam is red and it has lumps in.’ This is like saying ‘The horse should go forward into a light contact.’, or that ‘he should be “on the bit” with his poll as the highest point of his neck, and his nose just in front of vertical’. This left brain knowledge is the declarative knowledge which tells us what the horse should look like. But how many of us can ride our horses like this? With all the declarative knowledge in the world, we are still left wondering what good riding feels like, or what strawberry jam tastes like.

This discrepancy – between right and left brain knowing – has been the focus of my work for twenty years. The right brain thinks in pictures, feelings, sounds and rhythms (as well as tastes and smells), so it can help to talk to riders in images. These are bilingual, in that they speak to both sides of the brain. So I could get one step closer to solving this rider’s problem by telling her that the horse’s back, in its ideal state, is like a strung bow. The horse’s abdominal muscles are like the string on the bow, and as they shorten the back arches upwards, so that it acts as a bridge between the hind quarters and the forehand. The muscles on the underside of the neck then relax, and the crest of the neck reaches and arches into the rein.

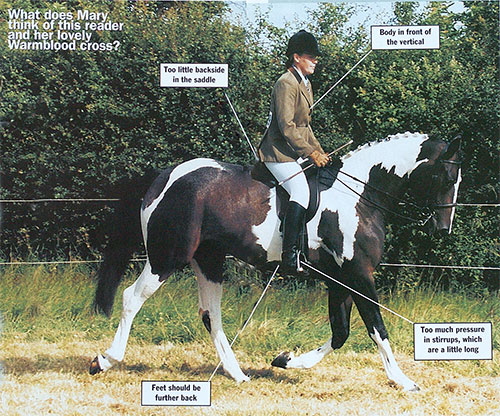

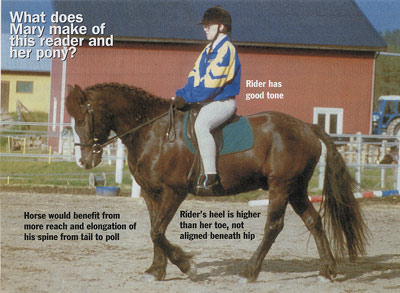

In the photograph, her horse is like an unstrung bow: the muscles of the belly and the underside of the neck are so long that the ‘wood’ (or top line of the horse) as actually inverted. This will not change until the belly muscles shorten. But the question which still remains is, ‘How do you get this to happen?’ Our traditions of riding teaching have not adequately addressed the ‘how’ of riding: declarative knowledge was supposed to solve our problems, but it never can. What we need instead is procedural knowledge, which tells us what we have to do to achieve that ideal result. It can give us a lived experience of how correct rider biomechanics work their magic on the horse.

If this rider rode into my arena, I could help her far more that I can from a distance. Somehow, I would endeavour to give her a taste of strawberry jam, and then I could say, ‘There, it’s that. That’s the feeling you’re going for.’ And then I would probably ask her, ‘So if you had to teach someone to do what you have just done, what would you say to them?’ Her answer would tell me which words and images work best for her – and we would be up and running.

To give her a taste of strawberry jam, I would have to get my hands on her body, and make adjustments to her sitting (giving her sensory as well as verbal input). In the photograph she looks quite pretty, and her leg is in an unusually good place; but her torso is the cause of her problems. First of all, she needs to bring her shoulders forward until she is vertical. Then, she needs to bring her ribs down towards her hips so that she is not growing tall. Next, she needs to learn to bear down, and to generate power in her body, so that she is more like one of those weeble dolls that you cannot knock over. She then has to use that power just like a martial artist – and it would help her immensely to learn a martial art.

I suspect that harnessing this power, and ‘lowering her centre of gravity’ will require her breathing pattern to change, and that she is an upper chest breather who will struggle to learn diaphragmatic breathing. Only this will enable her to sustain bearing down, which I have written about extensively in the other articles of this series, and in my books. In short, it is the change in your abdominal muscles which takes place when you clear your throat, cough, or giggle – but you have to sustain that change all the time (whilst also breathing!). This, in itself, is a massive shock to most riders. It is the cornerstone of good rider biomechanics, generating the core strength every rider needs.

Feeling these differences in her body – and struggling to maintain them – will set our rider on the path of her learning process. For I fear that despite her training, she has not yet set foot on it. She has to reinvent the wheel discovering for herself, and in her own body, what works. It is not enough to just hear the words, and to try to obey instructions. Teachers cannot tell you how to do it, and you cannot soak up their knowledge: they can only act as a tour guide, whilst you yourself take the tour, piecing together the cause-and-effect rules of riding, and discovering that ‘When I do A, the horse does B.’

Armed with this knowledge, our rider will not become confused between different ideas that are proposed by different teachers. Instead of relying on their authority, she will, with guidance, begin to develop her own authority. She will begin to understand that position is not a means in itself. It is not a way to sit on the horse and look pretty. Instead, it is a means to an end: it is the tool through which the rider does the job of shaping the horse. Once our rider has felt her horse’s back come up, she will know (in both halves of her brain) exactly what it is that she is talking about, and she will ride that talk effectively.

Meanwhile, there is one simple exercise she could do with a friend which might help her. Her friend, however, will need to be watchful for her safety, keeping an eye on the horse’s hind leg as she stands beside the girth, and puts her finger tips along the mid line of the horse’s belly just behind the girth. She then wiggles them as she presses up against the belly – and if necessary, she digs her fingernails into the horse. With any luck, the horse will lift her stomach and back, (but she may also cow kick). This will give the rider the feeling of what it is like to sit on the ‘strung bow’, and she may be able to maintain that feeling as she walks on.

She will need to learn to make her body like the weeble doll or the martial artist, but at the same time as generating this feeling of ‘down-ness’ or ‘heavyness’, she will need to think about drawing the horse’s back up underneath her. This is a paradox which I have explained at length in my books. I hope she can work this one out, or get help from someone who can specifically show her how – and I wish her well on her journey. The power o fboth understanding and living the power of rider biomechanics is enormous.