RWYM

ARTICLE 33

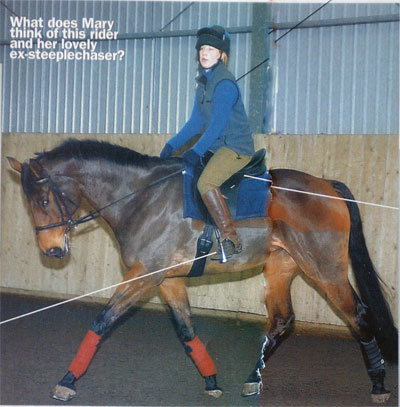

This photograph was taken at my riding centre this summer, and it shows a longer-term pupil from America riding my own thoroughbred mare Luby, shown here at twenty years old. This article is her epitaph, as she has since died. It would seem that she had a heart attack whilst cantering down the field, and although she looks pretty good in this photograph, a year with Cushings disease had taken a toll on her. Whilst her death has been a source of great sadness to me, I have to admire her timing. I also thank her for sparing me from what would (at some point in time) have been an agonising decision.

This photograph was taken at my riding centre this summer, and it shows a longer-term pupil from America riding my own thoroughbred mare Luby, shown here at twenty years old. This article is her epitaph, as she has since died. It would seem that she had a heart attack whilst cantering down the field, and although she looks pretty good in this photograph, a year with Cushings disease had taken a toll on her. Whilst her death has been a source of great sadness to me, I have to admire her timing. I also thank her for sparing me from what would (at some point in time) have been an agonising decision.

What a wonderful teacher she was, both for me and many others! If anything that I have found out about the biomechanics of riding deserves its place in history, so too does this horse. I have also learnt an enormous amount from riding a great variety of horses, and especially through my quick, ten-minute attempts to reorganise horses for my pupils during clinics. But Luby has been my main ‘laboratory’ for the last twelve years, and her sensitivity, her passion, and her need for a congruent rider have required me to become extremely precise. I am so grateful that she threw me this challenge.

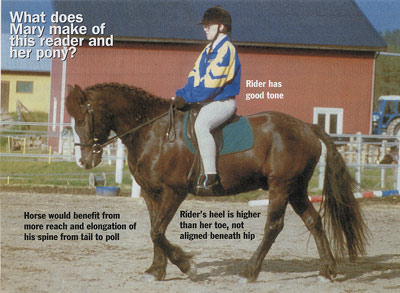

Beccy, pictured here, is in her forties, and came to riding as an adult. She has her own horse and good tuition back home, but she is relatively inexperienced and struggling with some of the basics. The biggest give-aways are her hand, which is lower than it should be, and her lower leg, which looks to be clinging on in a heel up-and-in and a toe down-and-out way.

In her youth Luby would not have tolerated this, and would have been off over the horizon. But latterly, when I have put riders on her who would in the past would have ‘pushed her buttons’ I have watched her start to ‘rev up’, and then seem to think ‘I’ll have to run away… well no, perhaps I won’t bother.’ When I bought her twelve years ago she was a nervous wreck, and the ultimate ‘motor-boat’ pony. Heaven help any rider who ‘water-skied’ – although in reality, she did most of her running away in extended trot (and I would not let anyone ride her in canter unless I thought they were stable enough to cope.)

For many years ‘she took me’ in most of our canter work. To understand this, think of riding a bicycle, and pushing round the pedals. You then generate the power that makes the bicycle go; but when you come to a steep downhill, you cannot pedal fast enough to keep up. Then, the bicycle takes you. Think too of using an electric sewing machine; if you get carried away when you put your foot on the pedal, the needle moves so fast that you cannot feed the material through quickly enough. Then again, the machine takes you.

By analogy, the horse takes you when you loose control of the speed at which its legs go around, i.e. the tempo. You take him when you are in control of that speed. This makes you feel that you can use your leg when necessary, and maintain a light rein contact. Most riders start to pull on the reins when the horse takes them, but this cannot slow down the speed of his legs. The chances are that it makes the horse claustrophobic so that he wants to get away from you – and if you then lean back in a misguided attempt to stop him, you also instigate the water-ski/motor boat dynamic. You may have thought you were saying ‘whoa’, but in horse-language you were actually saying ‘go’. Things go from bad to worse as the horse towes round the riding arena.

The only way to slow down the speed of the horse’s legs is to slow down your own body. If your horse speeds off with you at canter try counting to yourself, ‘te-tum, te-tum, te-tum’ in rhythm with his forelegs. This works best if your counting begins with the very first canter stride that he takes, and the effect is often miraculous. The fix also requires to you bear down, using your abdominal muscles in the same way that you do if you cough or clear your throat. Think of pulling your stomach in, making the muscles into a wall, and then pushing your guts against that wall.

This push is, I believe, what the term ‘push’ really means in riding, although so many riders assume that they should push with their backside, shoving it around in the saddle. Realise, however, how still good riders sit. The hidden ingredient of their quiet power (and their ability to take the horse) is bearing down. Less than 5% of riders do this naturally, and we call them ‘talented’. So check out what happens particularly in your lower stomach (where you will be especially tempted to just suck your stomach in), and whenever you are tempted to pull on the reins. When you change how you use your abdominal mucles, you change the whole dynamic of your interaction with the horse.

Slowing down the canter, and reliably reaching the stage where I could push my hand forward took me a long time. It took even longer to take Luby well enough to reach her into the rein in the way you see here. In fact, Luby was renowned for her phenomenal trot, and it took me a while to realise that despite our problems, she also had a phenomenal canter. Over a number of years as my skills became more reliable, her panicky, thoroughbred, motorboat tendencies subsided and gradually became dormant – only to be reawakened by a rider who reached her threshold of intollerance.

There is much to like about the canter shown here. Along with the crest reaching and arching from wither to poll, the angle under the gullet is very open, and the underside of the neck is soft. Horses so easily become tight under here, especially when the rider is too strong with her hand, and/or has used draw reins or other gadgets to keep the horse’s head down. This look is virtually impossible achieve when the rider is not in control of the speed of the horse’s legs and/or does not trust in her ability to draw the horse’s back up under her.

Beccy’s hand position, however, suggests that her faith in her skills is relatively low, and that she is scared of the horse coming above the bit. Her hand would have to be about level with the horse’s wither to give her the classic straight line from elbow to hand to mouth. When the horse’s back is hollow but the rider’s low hand attempts to hold his head down, the hand often creates the very problem it is supposed to cure. For (as I have explained in previous articles) the horse tends to raise his head against the contact – tempting the rider to hold it down more strongly and the horse to pull it up more strongly.

Beccy has the good fortune here to cash in on Luby’s previous training, and a chance to break the pattern, for the horse is established enough in good carriage not to be tempted into a battle over her head position. Riding a schoolmaster like Luby is a chance for Beccy to experience a more correct feel, and develop more rightness with her body, and less wrongness with her hand. If she could take away the most correct feelings she got from this experience, and imprint them onto her own horse, she would have achieved its ultimate benefit.

Raising her hand was actually easier for Beccy than letting go with her calf. My suggestions that she rotate her heel out and bring her lower leg away from the horse’s sides were hard for her to implement. In my experience, people are far more tempted to cling on with their lower legs in canter than they are in trot, and it is not an easy habit to break. More ‘goey’ horses may race off with them, and bearing down and counting the tempo will help enormously, although the fix will probably require a change in the leg as well. More lazy horses will tempt the rider into all sorts of contortions since her lower leg is not free to kick. In either case, keep correcting your body, and sending ‘let go’ messages to your lower legs. Then pray for the day that they actually respond!

I don’t like to think of Luby resting in peace. I like to think of her magnificent spirit cantering across the heavens, unencumbered by a body that was reaching its use-by date. As someone with an interest in Physics and Metaphysics, I also like to think that somwehere, somehow, in the parallel universes of space-time, we shall greet eachother again.