RWYM

ARTICLE 35

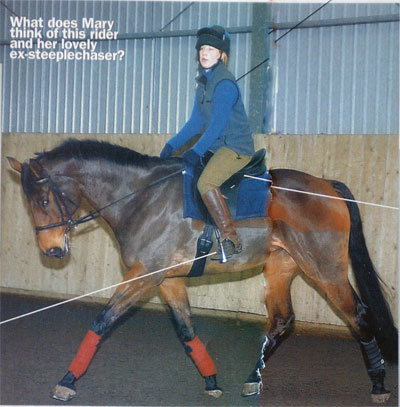

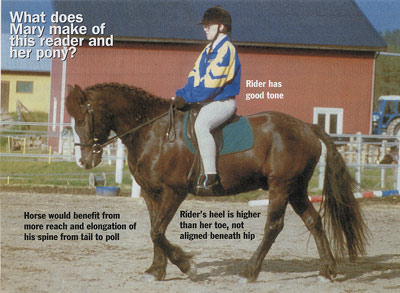

The photograph shows a seven year old Connemara pony, whose breeder gave her to the rider as a four year old. The rider tells me that ‘we have had much fun together competing in dressage, show jumping and cross country. We mostly do prelim and novice dressage, and in each of the last three years we have qualified for and been placed in our local riding club dressage finals. Our highlight was being placed in the six year old potential dressage pony championships at Addington last July. Misty (Padac Morning Mist) is a kind and genuine pony whom I feel honoured to have ridden.’

The photograph shows a seven year old Connemara pony, whose breeder gave her to the rider as a four year old. The rider tells me that ‘we have had much fun together competing in dressage, show jumping and cross country. We mostly do prelim and novice dressage, and in each of the last three years we have qualified for and been placed in our local riding club dressage finals. Our highlight was being placed in the six year old potential dressage pony championships at Addington last July. Misty (Padac Morning Mist) is a kind and genuine pony whom I feel honoured to have ridden.’

I too have a soft spot for Connemara ponies, as well as for Connemara/TB crosses, and have known many whose temperament and talent have endeared them to their riders. I also respect any small adult who decides that ponies are their forte, and I see far too many smaller people attempting to ride a big (fashionable) warmblood. Their relative size means that they would need consummate riding skills to do a good job, and it makes infinitely more sense to stack the odds in your favour through buying a horse or pony that fits you.

This photograph shows the third beat of the canter, with the diagonal pair still on the ground and the leading foreleg bearing most of the weight. Notice how horizontal the pastern is, showing the tremendous flexibility of the joints of the lower limb. Even on such an attractive pony, this is not a flattering moment to take a photograph – just as landing from a jump never makes such appealing photographs as take off or mid-flight.

From this angle we do not get such precise information as we would if the photograph was taken from directly opposite the rider (but we can see that the rider is smiling – quite a feat for someone who is cantering past the judge’s box!) The pony is reaching into the rein very nicely, with quite an even curve from the wither to the poll, which is close to being the highest point. The nose is slightly behind vertical, and this overbending is a common fault that is not easy to ride your way out of.

The rider is behind vertical, and herein lies her biggest problem. (Compare the angle of her upper body and also the front of the horse’s nose to the uprights of the fence and judge’s box.) Whilst her shoulder is behind her hip, her heel is in the right place under it, although she appears to be clinging on somewhat with her calf. If she could turn her heel away from the horse’s side and use discreet kicks to make her go forward, she would do a better job than she can by continuously holding onto the belly.

The better the rider sits to the canter, the less rock there is in her shoulders. Eliminating this rock is only possible on a good canter, for until the horse goes right the ride cannot sit right. However, it is equally true to say that the horse cannot go right until the rider sits right. This presents the most devastating catch 22 of riding, and all you can do is to sit a bit better, so that the horse can go a bit better, so that you can then sit a bit better etc. The rider has to set that ball in motion, improving herself to create a virtuous circle that makes the horse progressively more easy to ride.

What rock there is in the rider’s shoulders should go from vertical to forward and not from vertical to back. The ‘back’ part of the rock will happen, as shown here, when the horse’s forehand lowers on that third beat. So the rider will come forward to vertical during the flight phase of the canter, be vertical on the first beat of the outside hind, and come progressively further back with her shoulders as the horse rocks over his legs.

In the correct sitting mechanism, the rider is slightly forward on that first beat. The horse’s crest is then coming up towards her, just as it does when he takes off for a jump, and this is a helpful thought when you are teaching yourself to revamp your canter mechanism. Her shoulders then come progressively back as the horse rolls over his legs, so that she is vertical on this third beat. It is a small movement – not the exaggerated shoulder swing that one often sees in show jumpers – but this mechanism sets up the possibility of collection, whilst the rock that goes from vertical-to-back sets the horse up (or should I say down) to go on his forehand.

You might understand this better if you stand on an ‘on horse’ position, but with one leg slightly in front of the other. You are now positioned for canter right or left. Count the canter rhythm as ‘te-te-tum, te-te-tum’, and move your hip joint so that it opens as you count each sequence, leaving you behind vertical on each ‘tum’. This is the wrong (but instinctive) way to canter. Now do it the right way by bringing your hips back slightly in preparation for the next ‘te’. As you ‘te-te-tum’ bring your pelvis forward so that you are vertical on the ‘tum’. Your pelvis then comes back again to position you for the next stride. In this second alternative, notice how your shoulders can easily remain still. If you are riding in the first (wrong) way, the horse’s motion will make your shoulders will rock back as your pelvis rocks forward.

This means that ‘polish the saddle with your bottom’ (as some of us learnt in pony club) was bad advice. So is ‘use your seat to drive him forward’, as this too will tempt you to rock your shoulders back as you push your pelvis forward. The horse may go forward more, but he will certainly go down onto his forehand. ‘Think of a miniature fold down for a jump’ is better advice, as long as you think of the pelvis moving back rather than the shoulders moving forward.

Whenever I write about canter, I think of a conversation that took place during one of my teacher training courses. One rider said, ‘When I’m cantering, each stride feels like ‘Moz-am-bique, Moz-am-bique. Moz-am-bique’. ‘That’s terrible’ said another, ‘Why don’t you think of ‘tre-men-dous, tre-men-dous, tre-men-dous.’ I’ve got a much better way, said a third, ‘How about ‘Can-a-da, Can-a-da, Can-a-da’. I now go one stage further, and if I count the canter, I only count 1-2, 1-2, 1-2. The third beat will happen anyway, and I need my brain to be thinking ahead, ready to emphasise that next first beat.

This pony is very on her forehand (in Moz-am-bique). In a collected canter the outside foreleg leaves the ground just after it has passed the vertical position, and the horse does not roll down over its forelegs as you see here. Instead, it uses a braking action on both front legs to elevate its forehand, and enter the flight phase of the canter where all four legs are off the ground. This helps it to jump its weight back onto its hind limbs. (This information comes from the ground-breaking work of Dr. Hilary Clayton, who researches equine biomechanics at Mighigan State University.)

Being on the forehand is to be expected in a preliminary test; but to progress up through the competition grades, the horse has to change the mechanics of his canter, and the rider has to encourage if not initiate this change. But if the rider keeps rocking back, the horse keeps rocking down, and so it goes on… and on. The horse cantering like this is much more likely to be overbent, and meanwhile, anything that the rider does with her hand tends to worsen her plight. Pulling on the reins cannot make the horse change from rolling over his front legs to braking with them. She has to change the way that her pelvis, thighs and shoulders do their job.

Another helpful idea is to think of using your thigh as if you could lift the front of the saddle up off the horse’s back, and stop it from disappearing downwards on that third beat (along with the horse’s forehand). This would encourage you to keep the angle between your thigh and torso more closed, and this in turn helps you not to rock back with your shoulders. The more vertical your thigh becomes as you reach the third beat of the canter, the more you will be the victim of the horse’s dive onto his forehand, and feel that there is nothing you can do about it.

I hope these ideas will help our rider as she works with this lovely pony. Judges have obviously seen her potential, but so many good horses and ponies remain doing novice tests forever because their riders do not understand how to move beyond them and on towards collection. I hope our rider can work this one out.