RWYM

ARTICLE 42

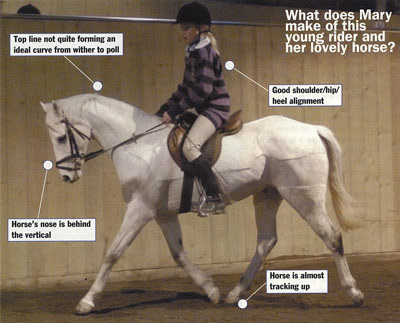

Here we have a pretty little Arab, working in quite a collected walk. From the fact that there is someone just barely in the picture, and from his demeanor – including the swish of his tail – I am wondering if his rider is building up to doing a more advanced movement, perhaps a walk pirouette or even a few half steps of piaffe. I can only quess at this however.

Here we have a pretty little Arab, working in quite a collected walk. From the fact that there is someone just barely in the picture, and from his demeanor – including the swish of his tail – I am wondering if his rider is building up to doing a more advanced movement, perhaps a walk pirouette or even a few half steps of piaffe. I can only quess at this however.

This picture is certainly a portrayal of focussed concentration from both horse and rider, and I this is what I most like about it. What worries me, however, is the shape of the horse’s neck, especially when contrasted with the shape of his body. The rider appears to be wanting a high head carriage – and she has much more contact on the bottom ring of her pelham bit than she does on the top one. It is never wise to sustain this for very long, since the horse’s lower jaw becomes trapped between the bit and the curb chain (which is bought into play as the shank of the bit rotates back). It can very easily go numb – so one constantly has to quard against an overly tight curb whenever one is working with two reins.

The shape of the horse’s neck is not the even curve from wither to poll that one would like to see. There is a sudden change in angle about two thirds of the way up his neck, with the upper third being much more horizontal. In fact, the point at which the angle changes is the highest point on the neck. This configuration is known as a swan neck, or as a break at the third vertebra. The horse who produces this evasion is using it to back away from contact with the bit, and although some horses seem particularly predisposed to doing this, it is often the result of the horse having been ridden in draw reins. I doubt if this horse has ever suffered that fate, however, and I get the impression that his rider has a very classical ethos. Like all of us who share this ideal, I am sure that she is involved in a life-long quest to gain the skills which will enable her to live up to her dream!

Once the horse has learnt to break in the neck like this, it is remarkably difficult to regain the ideal smooth curve from wither to poll, with the poll as the highest point of the neck. Lifting one hand can work as a short term correction – but it does not address the real issue, and one sometimes sees riders going along with both hands held really high, and the horse still managing to run this pattern!

The rider who uses her hand like this is aware that changes have to happen at the top of the hose’s neck, but unaware that they also need to happen at its base. If you think of the head as a weight on the end of a long pole, muscular work has to be done at the base of the pole to counterbalance that weight. The long back muscles which run under the panels of the saddle pass under the shoulder blades and attach into the bottom four vertebrae of the neck, and they (along with trapesius and other deeper muscles) are some of the most important muscles which are not working as they should.

When a rider is having this problem, I like to say “Imagine that we could perform a surgical operation, and insert a fishing rod just beneath the horse’s mane. If it had a small fish on the end of it, it would make a slight curve throughout its length. The whole length of his neck should ideally feel as if it really were hung from a fishing rod. But you may find that the rod has soggy bits, or even that it’s missing completely. What do you sense is happening here?”.

People can normally answer this question very easily, and you can probably imagine from looking at the photo that the fishing rod ends two thirds of the way up the horse’s neck. What is much less obvious is that the fishing rod will also be soggy at the base of the horse’s neck. This is the part which the rider must repair first – and amazingly, just thinking like this is often enough to fix the problem! Having reorganized the base of the neck the rider can then successfully think about the top of it (and if the “fishing rod” idea does not work for her I have several more images up my sleeve, one of which will usually do the job).

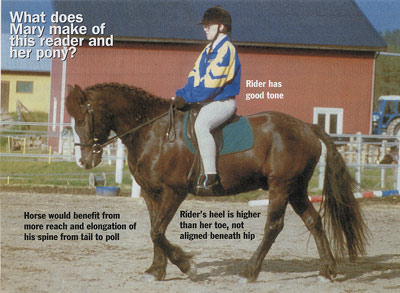

Horses find it very difficult to make the correct connection from the hind leg, over the croup, under the panels of the saddle, and up the crest of the neck. Think of this as an energy connection, or as water flowing through a hose. When complete the circuit continues through the rein to the rider’s arm and back, so that the energy received into her body rejoins the original conduit. This connection gives the rider a very correct influence, and enables the horse to seek a light contact with the rider’s hand, and, potentially, to “sit himself down”. How wonderful horses look when they achieve this! But it requires very skilful, correct riding, and the lengthening of the horse’s spine mirrors the “use” which people aspire to when they have lessons in the Alexander Technique

This horse breaks the circuit both at the base and at the top of the neck. He also is not “sitting himself down” – if anything I think he is raising his croup to evade this demand. Instead of maintaining the correct connection whilst shortening his whole frame as he would in collection, he has scrunched his neck backwards whilst lifting his croup. So things have gone rather awry – and as always, the rider is unknowingly playing a part in allowing this to happen.

She too has lost the ideal connection in her own spine, this time by stretching it too much and in the wrong way. From her waist she has separated both halves of her body, drawing her ribs up and stretching her legs down. If we could see the shape of her back, I am sure we would find that it is hollow. However, we all hear so much about “growing up tall and stretching your legs down” that our rider will almost certainly believe that she is sitting correctly! But I like to think of riding as a martial art, and this is not the stance used by good martial artists, who understand that this kind of stretching renders you much less stable and effective.

If you stand in a martial arts position and then exaggeratedly grow tall and lift your chest, you will find yourself all but holding your breath. You will also feel very tense and unstable. Then drop your ribs down towards your hips, so that you remove the hollow from your back. (Doing this sideways on to a long mirror will give you the clearest feedback.) For added strength, you can then engage your abdominal muscles in the way I call “bearing down”. Cough, giggle, or clear your throat, and then maintain that muscle use. Your major difficulty might then become breathing, for to bear down continuously you must use diaphragmatic breathing, which only seems to come easily to people who run, sing, or who have learnt to play a wind instrument. Many people who “grow up tall” are shocked by my insistence that they need to drop their rib cage. By comparison, they often feel slouched or round shouldered – so they are convinced that this new idea must be wrong. Some have heard the idea from the Alexander Technique that they should think of themselves “being pulled up by a string attached to the top of the head”. These words, however, are intended to describe a much more subtle expansiveness through the whole back and neck, which is not the same as this hollow backed version of growing tall.

The version of “stretching your leg down” which accompanies the wrong way of “growing up tall” becomes an attempt to get your knee beneath your hip to and make your whole leg vertical. This usually generates a strong pressure into the stirrup, which pushes the heel down and forward. If you are sitting in a chair as you read this, push one foot hard down into the floor, and realise how doing so tends to lift that side of your pelvis. Your body is obeying Newton’s third law of motion, which states that “every action has an equal and opposite reaction” ie. every push down will create an equal and opposite push up. This is one of the main reasons why people usually sit to the trot better without their stirrups – for they cannot then push down on them, and do not experience the straightening of their joints which then sends their backside up out of the saddle.

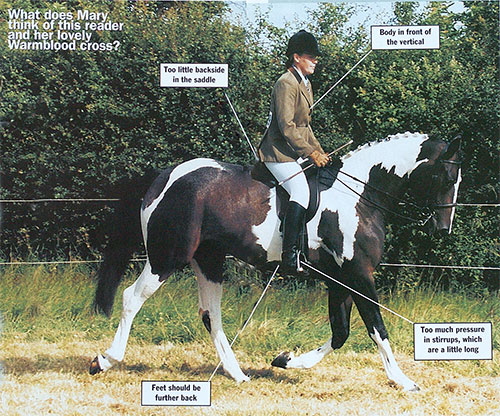

This bodily use opens the angle between the leg and the body too much, and it plays into the horse’s evasive pattern. (It would take me too long to explain to you exactly how this happens.) So to change her horse, this rider needs to change herself, completing her part of the circuit before she can complete his. I would like to see her bring her lower leg back underneath her and lighten her pressure into the stirrup. Creating a vertical shoulder/hip/heel line will make her feel as if her heel is back and up, and the change will probably horrify her! She also needs to spread the weight which does go into the stirrup over the entire width of her foot, and not roll her ankles over to weight the outside of the foot. The next step is to think of the thigh and calf making an arrowhead shape, in which the knee is the point of the arrow. This means that she will no longer be “stretching her leg down” in the way she is now.

Simultaneously, she needs to drop her ribs down towards her hips, and to take the hollow out of her back. This too may horrify her. It is as if she needs to shrink both ends of her body towards the middle – and into a martial arts stance. Then she is in a position for make the “fishing rod” idea work for her.

I wish her luck with this change, for I think that she will not find it easy – not because it is inherently difficult, but because it will feel so strange. But the pay-offs when she gets her little horse “connected” will be enormous, and I hope very much that she can do this.