RWYM

ARTICLE 38

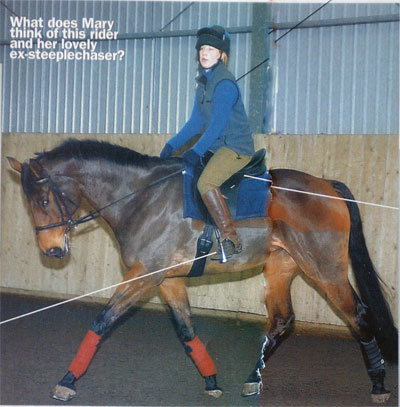

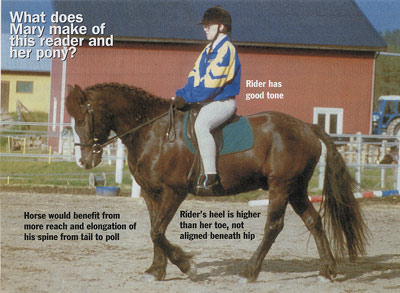

This horse is a six year old Irish Draught Thoroughbred cross, shown here in a preliminary test. His rider has, apparently, been reading my books and attempting to put theory into practice. ‘I have found so many things slotting into place’, she says, ‘and can feel so much more in control now when riding, and less as though I am bumbling about in the dark. There’s still a long way to go though; knowing what to do is one thing, doing it is another.’

This horse is a six year old Irish Draught Thoroughbred cross, shown here in a preliminary test. His rider has, apparently, been reading my books and attempting to put theory into practice. ‘I have found so many things slotting into place’, she says, ‘and can feel so much more in control now when riding, and less as though I am bumbling about in the dark. There’s still a long way to go though; knowing what to do is one thing, doing it is another.’

‘Doing what you know’ is the problem faced by riders whose theoretical understanding outweighs their practical skills. My work is an attempt to help people to bridge that gap more easily, mainly by using words differently, and creating descriptions of ‘right’ that help people get it. I am quite sure that if we had better ways to limit this discrepancy between theory and practice, there would then be many more good riders in the world. ‘Doing what you know’ is also an issue for riders who have discovered some facet of right, and need to keep reproducing that feeling. This can at first be a hit-and-miss process, for it takes 10,000 repetitions of a new co-ordination for that pattern to become ingrained in the nervous system. It then becomes an established habit that no longer requires conscious thought.

‘Knowing what you do’ is a problem for good riders who are such instinctive performers that they function on ‘autopilot’ and cannot describe their skills in words. It is also an issue for all of us who have quirks in our riding that we are completely unaware of. (We may think we are keeping our hands still, for instance, when actually we are not.) When you can ‘Do what you know’ and ‘Know what you do’ you probably have it made both as a rider and as a teacher or trainer. It is a noble aim that requires both brain hemispheres to work together, and very few people have the ‘whole brain knowing’ that this implies. When you can put turn words (theoretical left brain knowledge) into correct feelings (right brain riding skills), and can put feelings (those right brain skills) into words (to create helpful descriptions) you have a huge amount to offer. But since you will not then be thinking and talking down the conventional tramlines, the world may think you a little strange.

In her struggle to do what she knows, our rider has lined her body up quite well, although her heel against the horse’s side and her toe out suggests that her lower leg has got stuck in this place, and leaves me wondering how much control she has of it. People tend to cling on with their calves more in canter than in trot, and our rider really needs to attempt to rotate her toe in towards the horse’s elbows and her heels away from his sides, and to give her leg aids as discreet kicks.

A well-executed kick is like a slap that touches the horse’s side and then rebounds. Slap your own thigh, and realise that you make contact with it for a short time only. This is still true when you slap harder – although when people give a harder leg aid they tend to keep their leg against the horse for longer, turning it into a prolonged squeeze. This creates tensions that go up through the thigh and the torso. Done well, a stronger leg aid is simply a harder slap. Slap your thigh harder and demonstrate this to yourself. Then think of hitting the horse with the inside of your calf or ankle, and if you need a leg aid with real clout, think of hitting the horse with the inside of the stirrup iron. Then make sure that the leg rebounds immediately back to its starting position.

The rider has her stirrups a good length, with the thigh at about 45 degrees to the ground, and has a good line up to her spine. But she has not yet persuaded her horse to lift his back and reach his head and neck away from her. Although his nose is close to vertical, his back is rather hollow, and the low carriage of her hands suggests that they are trying to keep his head down. I suspect that if we suddenly cut the reins his head would shoot up in the air. His ears are pricked, so he may have just seen something and hollowed in response, but I suspect that he tends to work in this carriage – in canter if not in trot.

So how can our rider take that next step, bringing his back up so that he looks like a dressage horse? It is not so much that she is doing anything wrong; it is more that she is not doing it enough right, and I think she will have to establish that rightness in walk first of all. Even better would be to have a friend do a belly lift on her horse to give her the feeling of his back coming up. Then at least, she knows what she is looking for.

This may be best done for the first time in the stable, with no rider. Stand beside the horse’s girth area, and put both hands under his belly just behind the girth. Keep one eye firmly on his hind leg, since a horse who is in pain may well try to kick you. Then begin to press your fingertips into his belly, jiggling them slightly. You should see his back come up. If there is no change, suspect that his body is set in concrete, and that he will not be easy to influence when riding. If he is unhappy about it, begin to wonder if his muscles are in good shape. If his back comes up easily, he is potentially a good athlete, and the odds are stacked in your favour.

When you are mounted, the feeling of the horse’s back coming up is unmistakable. After a friend has done the belly lift with you in halt, your next task is to try to keep his back up as you walk on. Remember the difference between picking up a child who wants to be picked up, and picking up one who doesn’t. Then be sure that you are being a rider who wants to be picked up, and not a ‘sack of potatoes’ who does not take responsibility for her body weight.

To understand this better, stand on the ground in an ‘on horse’ position, and feel how this soon begins to make the front of your thighs ache. It is this use of the thigh muscles (aided, when you are riding, by the muscles on the inside of the thigh) which literally enables the rider to function as a suction device, drawing the horse’s back up instead of squashing it down.

Another factor concerns where the rider puts her attention, and I would like to ask this rider how much of her attention (out of 100%) is focussed on the horse’s head position, the feeling in the hand and rein, and whether his nose is vertical. If we ignore distractions and irrelevant thoughts (which should sum to zero) the remainder would be focussed on the shape of the horse’s back, and how her pelvis and thigh contacts his back. Along with this goes attention placed on her stomach muscles, and bearing down. This pushes her guts against her skin in a way which effectively pushes the horse’s head and neck away from the rider. (I described this in detail last month).

Many riders have confessed to me that 80 to90% of their attention is focussed on keeping the horse’s head down, and this actually stops them from learning how to use their thigh, back and stomach muscles to bring his back up. The hardest task facing them is to change their focus of attention, so that 80% of it is concerned with their thigh and pelvis, and the shape of the horse’s back. This can require an enormous act of faith, and I often help it along by asking, ‘Which is stronger, the push forward of your stomach muscles as you bear down, or the backward traction on the rein?’

When the hand is stronger the rider is riding the horse ‘front front to back’, and once the bear down is stronger she begins to ride him ‘from back to front’. This, along with the use of the thigh that turns the rider into a suction device, can enable very ordinary horses to do a fantastic imitation of the archetypal dressage horse – even though they may not have world-beating paces.

I hope our rider can increase her effectiveness through the way she focuses her attention, and by using belly lifts to give her increased sense of what it feels like when the horse’s back comes up. I also hope that she continues to feel inspired as more aspects of riding ‘slot into place’. After all, the whole point lies in enjoying the journey instead of longing to arrive. Travelling is not ‘half the fun’, it’s all there is.