RWYM

ARTICLE 39

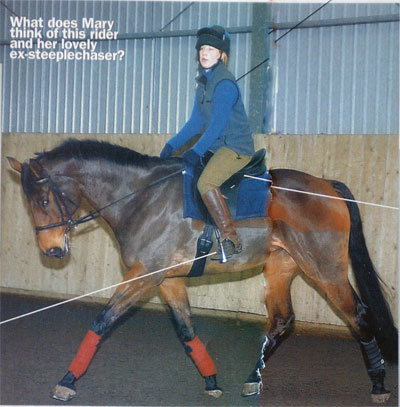

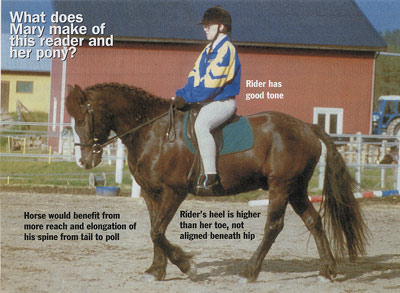

This is an 11yr old Irish sport horse who has been owned by his present rider for 3.5 years. He is shown here in a ridden hunter class, but does a bit of everything including dressage, show jumping, hunter trials and Le Trec.

This is an 11yr old Irish sport horse who has been owned by his present rider for 3.5 years. He is shown here in a ridden hunter class, but does a bit of everything including dressage, show jumping, hunter trials and Le Trec.

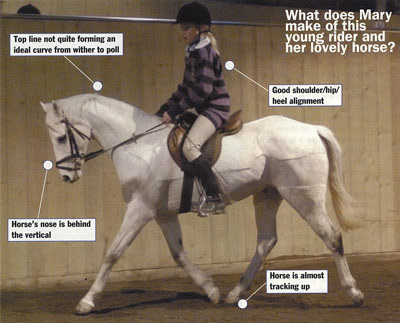

This horse and rider are close to being very good, and if we could get the overall picture slightly more right, they could look fantastic. The horse is close to tracking up, where the hind footsteps into the hoof print left by the front foot. He is quite well reached into the rein, with an even curve from wither to poll, and his tail is carried well. The angle under the gullet is nicely open even though he is fractionally overbent. (Compare the line of his nose to the dark upright on the tent just in front of him.)

The rider does not quite have the alignment that would leave her standing on her feet on the riding arena if we took her horse out from under her by magic. Her knee would need to come slightly more down and her foot more back to stop her from toppling backwards. However, she is resting the foot in the stirrup in a good way, and is not making the mistake of pushing down hard, and pushing her heel down and forwards in the process. So many people think that ‘heels down’ is the be all and end all of riding, but for flatwork it is a vastly overrated dictum. Be sure that you think of aiming your heel towards the horse’s hock (as this rider is close to doing) and not towards his knee (as so many people do).

I would love to see her without her jacket on so that I could be precise about the alignment of her back: I suspect that her backside is too tucked under her with her seat bones pointing slightly forward. The string from her number emphasises her waist, but despite this we only see an indentation in her front, and her back looks too straight. Within her structure, I suspect that she has very small spinal curves, and this will be a significant factor in her riding.

The spine naturally curves forward at the back of the neck, back between the shoulder blades, forward at the waist, back slightly in the sacrum (pelvis) and forward towards the tailbone. The degree of curvature varies for each individual, but the important factor is that those spinal curves remain in balance, without one curve becoming bigger and the others smaller. If you see a ‘banana shaped’ rider – whether the banana is curved forward or backwards – you know that one or more of the curves has been swallowed up by the dominant curve.

The vast majority of riders naturally have larger curves than you see here, and the danger with no curves is that we have ‘ram rod rider’. The danger with large curves is that we have an excessively wiggly rider who struggles to stabilise her spine. To test for whether your spinal curves are in balance, begin by noticing whether seat bones point straight down to the ground. Sit on your hands – both on a chair and on a saddle – to check this out.

The second test must be done with the rider sitting on a large strong box. The tester stands behind her on the box and pushes down on her shoulders, using straight vertical arms. When the rider is in ‘neutral spine’ that push will go straight down to her seat bones without deforming her torso. The round backed rider will deform by becoming rounder; the hollow backed rider will become more hollow (be careful as tester not to hurt her – make a very gentle push down). The rider may also have a side-to-side squishiness, which will be harder to identify and reorganise.

The tester will have to use her hands to guide the rider’s body closer to its ideal, and the feel for both parties is very clear when the rider has reached ‘neutral spine’. If you are not sure that you have reached it, you almost certainly haven’t, and it would probably pay you to book a session with a physiotherapist, Pilates teacher, or other body worker who can give you a clear sense of where ‘neutral spine’ is. This is such an important facet of skilled riding that it is worth investing in.

Another interesting feature of this rider’s conformation is her arms. Notice that she comes close to resting her elbows and lower arms on the top of her thighs. However tall she is, she has long arms for her height, and riding is much harder for riders whose elbows only reach their waist. Although our rider pretty much has a straight line from the bit via the reins to her hands and elbows, she would be much better off with her hands more up and out in front of her, her reins shorter, and her elbows ahead of the points of her hips. She would still have a (slightly differently angled) straight line, but would have much more margin for error. Right now, her elbows are jammed against her body, and if her hands come back for any reason, her whole body will come back with them.

Also, her hands are somewhat limp, and to change this I would like to place them in a more correct position with her thumbs on the top. I would then put my hands in front of her hands so that she could push her hands forward against the resistance I had created. I wood then ask her to reproduce this feeling. In reality, though, I think she might find this difficult, since the hand can only push forward when the body is ‘with’ the horse in every step he takes. This means that the rider must be able to match the forces which the horse’s movement exerts upon her, and I am not convinced that our rider can do this well enough.

The suggestions I have made so far are steps towards the big change that this horse and rider need to make. The bottom line is that they both need more ‘stuffing’. Notice how lean the horse is behind the saddle, and how pronounced his croup is in relation to his loins. (His croup may even be higher than his wither, which tips his weight onto his forehand and makes him harder to collect.) Imagine how fabulous he would look if we could blow him up with a bicycle pump, until he was ‘bursting out of his skin’.

This describes the ‘stuffed’ horse with higher muscle tone, and on occasion you have probably felt your horse ‘stuff himself’, growing higher and wider underneath you. When this happens the horse is often prancing and dancing and feeling a little scary: but imagine all that energy under your control, and imagine that you too were ‘stuffed’ enough to match it, and channel it effectively. The presence of both horse and rider would catch everybody’s eye, and you would have a good chance of winning your class.

If this horse and rider were two people shaking hands, I think they would both deliver a rather limp handshake. I cannot tell who has trained who into this limpness, or whether they were born as a perfect match for each other! But I do know that they both need to firm up, becoming more stuffed, and delivering more power. Think of the rider as someone that you (the horse) shake hands with. Neither a limp rider nor a rider who squeezes you would fill you with confidence and bring out the best in you. Like a hand shake that is ‘just right’, the skilled rider holds the horse’s barrel and manoeuvres him into place without slithering about, letting go of him, or crushing him. Everywhere the horse goes the rider goes too, maintaining that ‘hand shake’, and actually leading the dance instead of just following.

To sum up, my suggestions to this rider are that she finds the adjustments that will bring her into a correct shoulder/hip/heel vertical line, and ‘neutral spine’. This will bring her feet back, her waistband slightly forward, and make her feel that her backside is out behind her. Her hands need to push away from her body, and to increase the tone in herself and her horse she needs firstly to bear down more (see previous articles), firming herself up so that she can firm up him up too. When she can stay in balance, give her hand forward, and ride with more power, she will move her work up a notch and become a force to be reckoned with!