RWYM

ARTICLE 12

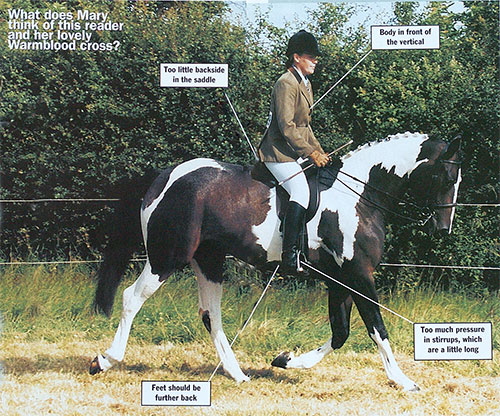

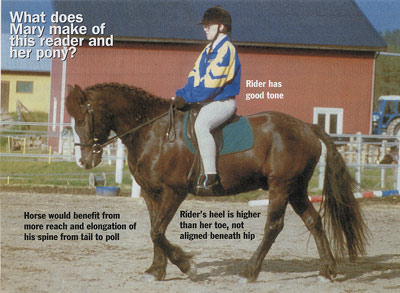

This photograph shows a six year old Warmblood x Connemara mare, ridden in her first dressage test, which is being held at a local show in Austria. (‘Horse and Rider’ obviously gets around! How I wish that my local show were held within such a beautiful setting!) The young girl riding her helps the horse’s owner, and has little professional help with her riding.

This photograph shows a six year old Warmblood x Connemara mare, ridden in her first dressage test, which is being held at a local show in Austria. (‘Horse and Rider’ obviously gets around! How I wish that my local show were held within such a beautiful setting!) The young girl riding her helps the horse’s owner, and has little professional help with her riding.

What a nice horse, who shows the Connemara stamp, and probably has the athleticism and cleverness which make Connemara crosses so versatile and popular. It looks from the photograph, however, as though her croup may well be higher than her wither, which gives her a physical disadvantage to overcome. It is hard to know from the photograph how much this is really the case, or how much the croup looks high because of the knock-on effects of the mare’s hollow back.

This leaves the horse unable to track up, and the hind hoof which is advancing will land on the ground well behind the hoof print left by the front foot. To understand the relationship between this and the hollow back, bend forward from the hips, with your back as flat as possible. Then attempt to hollow your back, and at the same time lift your chin and look up. This position (in which you are ‘above the bit’) is not comfortable, but you really discover its limitations when you begin to walk. Feel how restricted your ‘hind legs’ are! Then take the hollow out of your back, round it slightly and lower your chin. As you walk in this position, you have far more freedom of movement. So it is with the horse.

First shows, of course, rarely reveal one’s best moments, and as the horse’s owner states in her letter to me, ‘they were both a little nervous.’ She felt that ‘they coped extremely well, even if not as relaxed or quite as good as at home’. The mare is looking at the view with her ears pricked, so the rider’s first task is to get her attention. Although the line of her crest is still curved, she is not actually reaching into the rein: she is backing off that big unfamiliar world, and contracting her head back into her neck, her neck back into her wither, and her wither back into her back. The net result is that her back drops, making the hollow which most riders fall back into.

This has happened to our rider here. She is basically in an ‘arm chair’ seat, with her feet in front of her, her weight in her backside, and her shoulders back. If we cut the reins she probably would not actually topple backwards, but she certainly does not have responsibility for her own body weight. (If she did, she would land on her feet and not her backside if we took her horse out from under her by magic.) She is squashing the horse’s back down, perpetuating that hollow. All of these issues violate the basic principles of rider biomechanics: the rider is hindering her horse, not helping him, and somehow she has to learn how to make her body act like a suction device that can draw his back up under her.

The first step in this is for her to realign herself to show a shoulder/hip/heel vertical line, which means in practice that she would land on the arena on her feet. This is one of the base-lines of good rider biomechanics. The change would make her knee cap point much more down towards the ground, and not forward as it does now. Her weight will be spread down her thigh, and not taken so much on her backside. Her feet will be further back, with her heel less down. The horse’s owner could help her to do this – it does not take a degree in rocket science, only good will between both rider and helper. But the change will make our rider feel as if she is toppling toward with her feet way back, so a video camera would help to convince her of the rightness of this ‘weird’ new feeling.

This is where arguments develop between riders and their helpers/trainers /instructors. Few people appreciate that this kind of change always feels far bigger than it looks. They believe their body, which finds this ‘weirdness’ very hard to tolerate, and do not believe their teacher – who thinks that the change must surely feel as wonderful to the rider as it looks from the ground. So teachers often cannot understand why it is that riders keep trying to retreat from this new feeling (which is either weird or wonderful, depending on your perspective), back into the familiarity of ‘home’.

I often find myself reminding riders that when you loose a filling in your mouth, it leaves an indentation that feels to your tongue like a yawning great chasm. But it looks in the mirror like a very small hole. The same effect happens when you make changes in your riding: they feel huge, but look rather small – and if the change feels reasonable and appropriate to the rider, the helper/trainer/ instructor can often barely see a difference!

The next step is for our rider to support her own body weight more effectively. To understand this, think of the difference between picking up a child who wants to be picked up, and picking up one who doesn’t. If the child makes herself into dead weight she feels phenomenally heavy, and this is because all her muscles are relaxed. Supporting your own body weight requires more muscle tone – the same tone that allows dancers to jump, defying gravity in a way which a drunkard (one of the ultimate examples of low tone) could not do.

Between high and low tone lies a continuum in which the muscles are more or less firm. Having naturally high tone is a tremendous help to riders because of the precision and stability which it gives them. If your body is naturally ‘flopsy’ you have a much harder time organising it – although with practice and determination you can improve your tone phenomenally. Our rider probably does have higher than average tone, but she has not yet realised that she has to cultivate this quality. Like most riders, she probably doesn’t even know that this continuum exists or that she should strive to be anything other than at the relaxed (or ‘flopsy’) end of it. This is sad, since high tone is such an important aspect of good rider biomechanics.

It would probably help her to stand on her feet in an ‘on-horse’ alignment. She would soon begin to feel the strain in her thighs that should also accompany good sitting. I am sure, right now, that she would not experience this because it is the horse and not her thighs which are holding her up. She is relaxing whilst the horse takes the strain.

So, it will take realigning herself, taking responsibility for her body weight and then bearing down, for the rider to have the effect of drawing the horse’s back up instead of squashing it down. Through bearing down (pushing her guts against her skin, just as you do when you clear your throat) she will have to make a push forward which is bigger than the horse’s push back. In theory, this should not be too difficult, as the horse’s push back does not look enormous. However, appearances can be deceptive, and you never really know until you ride a horse how entrenched he is in his patterns.

Whenever I go in the world, I see many riders who, like this rider, are behind the correct balance point. From the horse’s perspective, the adjustments which will bring the rider’s centre of gravity over the horse’s centre of gravity make her a burden which becomes much less disturbing, and easier to carry. In theory at least, this change in the rider’s biomechanics is all the horse needs in order to perform that bit better – so good luck!