RWYM

ARTICLE 16

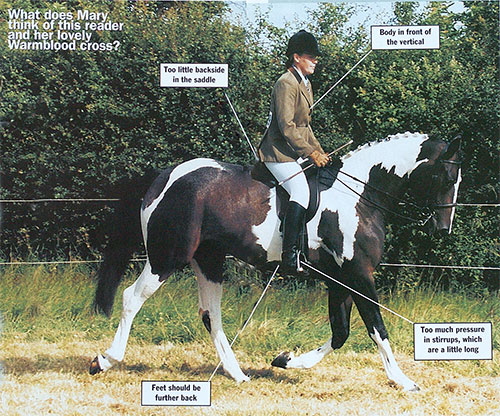

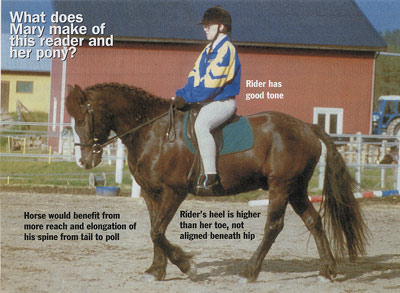

The horse shown here is a Connemara/Standard bred cross, who is aged nine. His owner and rider is aged sixty-five, and living proof that it’s never to late to learn and improve. She started riding at fifty-seven after a life time of longing to be around horses, and has owned her horse for six years. This means that she bought him at three and a half! At the time she believed that he was four and a half – but either way, she was pushing her luck as a relative novice buying her first horse. She tells me that she has fallen off him fifteen times, and that the two worst falls led to a broken collar-bone and to concussion! She must be one plucky, determined lady, and I am glad to hear that her persistence has been rewarded. For she now feels extremely lucky to own such a nice horse, and that she has a good rapport with him. She enjoys schooling, and feels comfortable hacking him out alone or in company.

The horse shown here is a Connemara/Standard bred cross, who is aged nine. His owner and rider is aged sixty-five, and living proof that it’s never to late to learn and improve. She started riding at fifty-seven after a life time of longing to be around horses, and has owned her horse for six years. This means that she bought him at three and a half! At the time she believed that he was four and a half – but either way, she was pushing her luck as a relative novice buying her first horse. She tells me that she has fallen off him fifteen times, and that the two worst falls led to a broken collar-bone and to concussion! She must be one plucky, determined lady, and I am glad to hear that her persistence has been rewarded. For she now feels extremely lucky to own such a nice horse, and that she has a good rapport with him. She enjoys schooling, and feels comfortable hacking him out alone or in company.

She is shown here in canter left, photographed whilst riding a preliminary test. I am impressed by the organisation of her body – in terms of rider biomechanics she is sitting well, and is doing a lot right. She has her stirrups a good length, and has a good arrowhead shape to the thigh and the calf (in which the knee is the point of the arrow). Her foot is resting securely but lightly in the stirrup, and she is not making the mistake of pushing down so hard that she creates an equal and opposite force which pushes her backside up. She is very close to the alignment where she would land on the riding arena on her feet if we took her horse out from under her by magic. She is also very close to having a ‘square bum’, in which the backside appears to have corners rather than a rounded curve. (This comes much more naturally to men.) She would probably benefit from having her reins just a fraction shorter, but there is a good line from her elbow through her hand to the horse’s mouth, and whilst there is some resistance in the horse’s mouth, she does not appear to have too strong a contact.

I am encouraged by many of the photographs and letters that I have received recently. For they have shown riders with good basic rider mechanics, who are obviously thinking well about the issues posed by riding, and by their particular horse. They appear to be working on their riding in constructive ways, and have even made me wonder if the water that I attempt to drip on the rock might be making a small indentation! My congratulations go particularly to those at the older and younger ends of the spectrum, and I really feel for those people who, like the rider pictured here ‘only wish that I was years younger and had many more years of riding ahead of me than I obviously have’.

The photograph we have here shows the horse reaching tentatively into the rein, but not showing the rounded top line that one would ideally like to see. The issue for this rider is to bring more strength and power – predominantly more bearing down – into an already good alignment. For this will increase her influence on her horse. However, there is one possible problem. I have watched many videotapes of riders using slow motion analysis, and from this I know that our rider’s position at this phase in the canter stride gives us little indication of the extent to which she will tip, rock and bounce in the other phases of the stride. If she is able to remain upright with her backside in the saddle throughout each phase then I take my hat off to her, and the next step of influencing her horse more profoundly will not be difficult.

The horse is pictured with the diagonal pair of legs on the ground, and the leading foreleg about to become weight bearing. This is the phase in the canter stride in which the horse’s back is relatively level, making it easy for the rider’s torso to be vertical. Our rider looks to be just a fraction behind that ideal. Although it is possible that she will stay here throughout the canter stride, it is more likely that she has been caught at about the most flattering moment of a sequence in which her shoulders rock forward and back.

In both trot and canter the horse’s back moves up and down rather like a sine wave, but in canter his body also tips and rocks as it moves between the extremes of the nose up and the hind quarters down (in the first beat), and the hind quarters up and the nose down (in the third beat). As a result of this, the rider’s shoulders also tend to rock. The better the rider’s biomechanics, the less this happens.

As the horse’s weight is transferred to the leading foreleg, photographs (of even the best riders) get that ‘downhill’ look. As the horse’s neck drops down, the rider’s shoulders tend to rock back. The slight lean back of our rider in the second beat of the canter (where the back is level) suggests to me that this will happen to her. But therein lies a problem, for leaning back puts the rider into ‘water-ski’ rider biomechanics, which in turn encourages the horse into ‘motor boat’ biomechanics. As she rocks back, he dives more and more onto his forehand, and as a consequence she leans back even more. The further they down go down this spiral, the more she cannot rebalance him (and sometimes, the more she cannot stop him).

As well as rocking, many riders also bump, with the back of their backside leaving the saddle. In the ‘up’ phase of the stride, they go up with the horse; but when he begins to come down, their momentum keeps them going up. One of the secrets of sitting well lies in turning ‘up’ into ‘down’ at just the right moment. Since gravity alone will not bring you down at the right time, you literally have to pull yourself down by pulling down your shoulders and rib cage. Only this will keep you in contact with the saddle.

Really good riders barely move their shoulders at canter, and this requires not only good rider biomechanics, but also a canter which has enough quality to be sittable on.

This of course, is the ‘catch 22’ of riding, for until the horse goes right, the rider cannot sit right; but until the rider sits right, the horse will not go right. The upshot of this is that the art of riding lies in making the horse easy to ride – which always seems so unfair to the novice rider, who needs all the help she can get. In reality we all have to work our way through this one, sitting a little better so that the horse goes a little better, and then sitting better still etc. This is the way in which our rider pictured here will improve.

Here is a quick exercise to help your backside stop bumping in canter or trot, or, if you already sit well, to add more power to your line-up. Reach around the front of your body with one hand and grab the muscle just below the back of your armpit. Now pull down your shoulder and elbow, and feel the muscle bulk out. How far down the side of your torso can you feel that bulk? In theory, it should extend all the way down to your pelvis – but this is only the case for someone with strong ‘Lats’ (short for latissimus dorsi). You can strengthen them by pulling down your shoulders and elbows as you drive your car. These are phenomenally important riding muscles, and by pulling down on your shoulders you help to combat the effects of your momentum, turning ‘up’ into ‘down’, and holding your backside in the saddle.

Also, imagine someone floating along behind you with her fingers just under your armpits, pulling back on your ‘lats’. You have to pull away from her, keeping yourself vertical. (Try this with a partner when standing.) This will strengthen the force that you generate from the back towards the front, helping you to match the forces which the horse’s movement exerts on your body. You can then stay ‘with’ the horse, and you are no longer tempted to pull back on the reins. ‘Lats’ can also help you to combat your asymmetry – when they are strong, it is as if a broom handle were strapped onto each side of your body, stopping you from collapsing and shortening one side. I can barely begin to communicate to you how important these muscles are. Start strengthening them now!