RWYM

ARTICLE 18

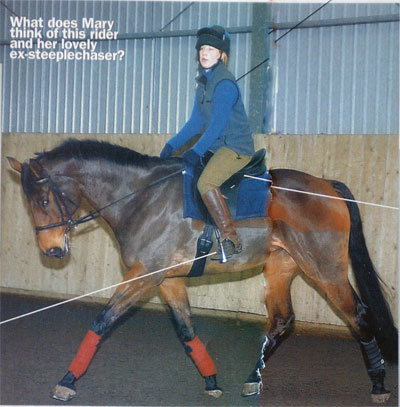

This horse is an eight year old 17.2 h Irish gelding, who has been hunted each season since he came over from Ireland as a four year old. His owner tells me that ‘I have never found a hedge/wall or any other obstacle that phases him’, and also that ‘flatwork has not been foremost in my mind’. He hunted less last season and has not been turned away for the summer, so she and a friend (pictured here) have been ‘playing with him’ with a view to dressage or eventing.

This horse is an eight year old 17.2 h Irish gelding, who has been hunted each season since he came over from Ireland as a four year old. His owner tells me that ‘I have never found a hedge/wall or any other obstacle that phases him’, and also that ‘flatwork has not been foremost in my mind’. He hunted less last season and has not been turned away for the summer, so she and a friend (pictured here) have been ‘playing with him’ with a view to dressage or eventing.

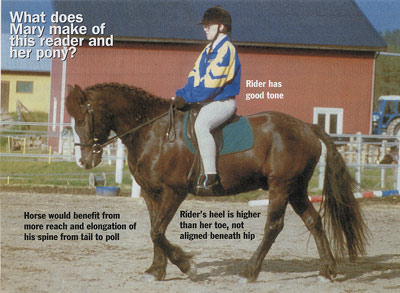

This is a lovely big horse, who I imagine from his type and boldness could have done well in many spheres. This is one of four photographs, and it is probably the least correct of them – but it has many lessons to teach us about rider biomechanics. In the other photos the horse looks less scrunched, but still overbent. The owner does not tell me anything about her own or her friend’s riding (but I surmise that she herself must be a gutsy rider across country). If you point this horse in the right direction, he obviously jumps anything; so I wonder if his owner realises that in flatwork, how the horse goes is the result of his interaction with the rider, whose biomechanics have a phenomenal influence over the final result.

It is also true that riders for whom speed and risk are the most sought-after elements in riding tend not to enjoy the quietness and slowness of dressage training. Riders who hunt and jump have to focus their attention externally, leaving their body to function on ‘auto-pilot’. They need high adrenaline to get the ‘buzz’ that makes horses worth riding, and they typically find that going round and round in circles is boring. The introvert who is attracted to this is often overwhelmed by the sensory input of speed and an unknown terrain, and she is far more aware of danger. Her ‘buzz’ lies in the subtle interaction of the rider biomechanics with the horse’s way of moving. She finds excitement in a sport that (to others) can be like watching paint dry. She is often a ‘control freak’ – the direct opposite of the ‘adrenaline junkie’.

These two psychology’s represent such different ways to ‘tick’ that few people excel in both of them. Very few riders compete at the highest levels in both jumping and dressage. (Chris Bartle and Reine Klimke are two exceptional riders who have.) So the biggest challenge that faces this horse’s owner (if not her friend) may well be the shift to an internal focus of attention, finding clarity and fascination in an a quiet inner space that is not fuelled by adrenaline.

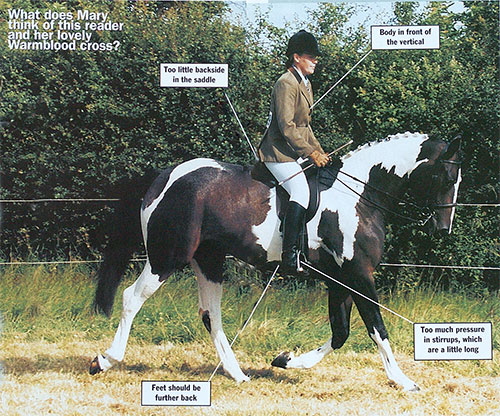

Some of the world’s most respected trainers have been known to declare that in flatwork, 95% of the picture that you see is attributable to the rider. This demonstrates the enormous power of the rider’s biomechanics. This influence may occur by default or by design, and in the photograph I fear that it happens by default. The horse is shown in canter right, with the outside hind leg on the ground. The most striking thing about him is that his nose is behind vertical, with a very tight inverted ‘V’ shape under his gullet. I suspect that his nose is slightly tilted towards us, and that the rider is slightly twisted towards us, with her outside shoulder in advance of her inside one. This creates a complicated interaction of asymmetries, which I do not propose to talk about. The contact on the rein appears strong, and the rider’s low hand position is suspicious. What would happen if she raised her hands and gave them forward? Would the horse shoot off, or would his nose go up in the air? I suspect that either or both of these would happen.

The rider’s fleece hides her back, but I am sure that she is round backed. Her front looks shorter than her back, and she is leaning slightly forward. But the photograph may illustrate one moment in a backwards-and-forwards rock of her shoulders. We discussed this several months ago, noting that the rider’s backside often isn’t in the saddle at this point in the canter stride, which this rider’s is (all credit to her). From being maximally ‘up’ in the period of suspension, the horse has lowered his quarters to weightbear on his outside hind. Commonly, riders do not turn ‘up’ into ‘down’ quickly enough to drop down with the horse, so they come down late. This is the structure of bumping.

So whilst the rider deserves all credit for not actually bumping, there are other problems. The rider’s armpits are closed more at the front than they are at the back, and I think she would have some creases under her sternum. Her lower leg is forward, so that if we took her horse out from under her by magic, she would not land on her feet. Her whole leg has a wishy-washy look to it – its tone is low, and the place of greatest strength in her body is her arms.

In her defence, this horse may not be easy to ride. If he sets off around the school as if he were going hunting, it would not be easy to remain in charge, and to call on the strength of your body and not your arms. The following corrections may seem obvious, but it would be naive to assume that the rider could easily follow my instructions if I told her to close her arm pits at the back, bring her shoulders back, and lengthen her front so that she lost those creases. It would be even more difficult for her to bring her leg back under her and give her hand forward.

I like the way that trainer Baron Blixen von Finicke has said that the rider has to ‘fight the battle for position’. This is not the same as fighting a battle with the horse, and as soon as you find yourself doing this you have ‘lost it’. This may have happened to our rider here. The key issue of riding is whether you can maintain your rightness in the face of the horse’s wrongness. Riders with good biomechanics do this far more effectively, but often the rider becomes so disorganised by the horse’s movement that she cannot make the corrections she needs.

The bottom line in riding is that you cannot really control your body until you can match the forces which the horse’s movement exerts upon it. For the horse kicks you up the backside in every stride, and our rider is clearly (to my eye) not a match for the forces acting. Once this happens the rider will – by default – pull on the reins. The only alternative to this force, which acts from the front towards the back, is for her body to create a force from the back towards the front. When this ‘push’ matches the thrust of the hose’s hind leg, the rider can give her hand forward. This is a key tenet of rider biomechanics. Doing the following exercise will transform this rather esoteric idea into an understandable, achievable reality.

Take a bath towel, or a sweat shirt or fleece that you can roll up, and put it around your back under your arm pits. Then hold on to the ends of it, and stand in an ‘in horse’ position. If you can, stand sideways on to a long mirror, so you can check that you do not lean back or hollow your back. Keep your shoulders and elbows down, and pull on the towel at the same time as you push back into it. Do this for at least a minute before you move the towel slightly lower down. Repeat this, until the towel is finally around your pelvis. How does this exercise change your back and your abdominal muscles? You will find yourself using your abdominal in the way I call ‘bearing down’, and you will also discover the true meaning of that old phrase ‘use your back’.

The muscle strength that you generate as you do this is the missing piece for our rider, and once she has this she has far more chance of ‘fighting the battle for position’, and winning it to the extent that she can make the corrections I have suggested. Then, she will be able to push her hand forward. Good riders who tell you that they are ‘doing nothing’ are, in effect, doing this exercise on horseback. Imagine how much more easily this firmer body would stay in place, compared to that of a rag doll. Once pushed out of place, the rag doll grabs the rein for security, and she is then told that she is too tense. But the bottom line is that she does not have enough tone in her torso. How I wish that this baseline of good rider biomechanics was more widely understood.

Our rider will also need this tone in her legs, and that may be less easy to gain. But by the same principle, the more they are firm instead of flopsy, the more they will come under her control. The horse’s owner may well loose her position in a different way. She might, for instance, be hollow backed. But it is a sure bet that she is also unlikely to be able to match the thrust of this horse’s hind leg, so this must be her primary aim.