RWYM

ARTICLE 20

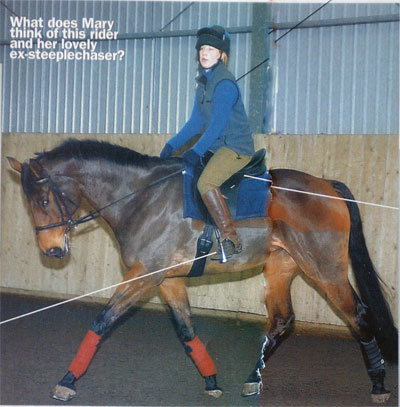

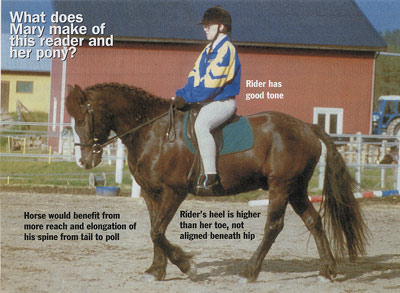

This photograph shows a difficult mare, purchased by the owner four months previously. She was in fact one of the demonstration horses in my lecture series earlier this year. Much to her rider’s amazement she behaved quite well, for she has been pretty scary to ride, and rehabilitating her has been a challenging experience. Unfortunately I am not absolutely sure of her age and breeding, but believe that she is an eight year old Thoroughbred type.

This photograph shows a difficult mare, purchased by the owner four months previously. She was in fact one of the demonstration horses in my lecture series earlier this year. Much to her rider’s amazement she behaved quite well, for she has been pretty scary to ride, and rehabilitating her has been a challenging experience. Unfortunately I am not absolutely sure of her age and breeding, but believe that she is an eight year old Thoroughbred type.

The rider has had a small amount of input from one of my trainee teachers, and is making a good attempt to ride in the shoulder/hip/heel alignment of good rider biomechanics. She would not quite land on the arena on her feet if we took her horse out from under her by magic, but would come very close. She is slightly in front of vertical, and is wearing so many layers of clothing that we cannot see the shape of her back. She may be slightly hollow, but again she is not far off the ideal of ‘neutral spine’. In this, the spinal curves (which are more or less extreme in different people) are balanced, and the rider’s seat bones point down. If someone were to exert pressure straight down onto the rider’s shoulders, that pressure would compress her torso slightly without deforming her spine. In contrast, the round backed rider would become more round backed under that pressure, and the hollow backed rider would become more hollow backed.

If you want to test this with a friend, be sure that you use a strong chest or table that will support both of your weight as one of you sits on the edge of it and the other stands on it behind her. As the tester, press straight down on the rider’s shoulders, using straight elbows and your shoulders directly above hers. Begin with gentle pressure that you gradually increase until it becomes clear how her body will deform. This deformation can be uncomfortable for the person who is hollow backed, so go very carefully. Between you, you then have to work out how to sculpt the rider’s body so that it will not deform under that pressure. Without experience this can be tricky, but when you get it right you will both know, for tester and testee experience an unmistakable feeling as the pressure on the rider’s shoulders is transmitted straight through to her seat bones.

This is a very educational experience from both perspectives, and if the rider can stack her torso in the same way when riding, she will undoubtedly find great benefit. Be aware that there should be a very slight forward curve at the waist, a slight backward curve between the shoulder blades, and a slight forward curve to the neck. Our rider in the photograph has her head in front of the ideal plane (as most riders do) and she needs to remember that her ears should be stacked up over her shoulders, hips and heels. Also, her shoulders are more rounded than the ideal, and it would help her to think of closing her arm pits at the back, which will flatten her shoulder blades against her back and open her chest.

Mary riders and teachers do not realise that the upper back can curve either forward or back (bringing the neck and shoulders in front of or behind the back at bra-strap level), and also that the armpits can close or open at the back or front. These two corrections are commonly confused, and round-shouldered riders are often asked to bring their shoulders back without changing their armpits. In a mix-up created by poorly understood rider biomechanics, this creates a rider who ends up leaning back, with rounded shoulders! The rider then has to stick her head forward to compensate for the fact that she is leaning back, so she becomes even more contorted. The neutral spine exercise cuts straight through these problems (and through a lot of self-generated back pain), and I recommend it highly. If the corrections you need to make are too complex for you and your friend to master, consider paying for a session at your local physiotherapy clinic to teach you how to stack yourself up in ‘neutral’. Very few of us do so naturally.

The horse in the photograph has been so scary to ride that our rider may well be in ‘survival mode’, reminding herself to breathe deeply and to keep bearing down – the two primary antidotes to fear. Thus there may be little ‘brain space’ left for her to remember about her position. But she needs to keep in mind that her rider biomechanics are a means to an end, and not a means in itself i.e. it is not just for looking pretty, they are the primary tool in the rider’s tool kit for riding the horse. The first tools in this tool kit are alignment and bearing down, and after these comes ‘plugging in’ – reducing your seat bone movement so that it is an exact match for the movement in the horse’s long back muscles. This connects the rider to the horse’s body, and also to his brain and his energy system in a way which makes him much more ridable.

Any extraneous movement in the rider’s seat bones creates a disconnection, and is like the static in a radio that is not correctly tuned. So think of halving your seat bone movement, and if necessary of halving it again. There should not be any wiggles and jiggles visible in your waist area, and there should not be any ‘shove’ in your seat bone movement. Just mould on to the horse’s back. Become aware of the line of flesh across the back of your backside, where it parts company with the saddle. You do always have the same bit of ‘flesh in contact with the saddle throughout each phase of the horse’s stride, or do you wiggle from one bit of flesh to another? You are not truly plugged in until you always have the same line of flesh in contact with the saddle. The rewards of this are huge (especially on whizzy and scary horses), so be strict with yourself as you search for it.

Two things strike me about the horse in the photograph, who is pictured in walk. Firstly, there is much more horse behind the saddle than there is in front of it, and she has a tight ‘V’ shape under her gullet, instead of a more open ‘U’ shape. If she were a stuffed toy horse, she would have far more stuffing in her back end than she has in her front end. The rider has to get more stuffing up her neck, and this will translate into not only a more beautiful horse, but into one who is more inclined to say ‘yes’ than to say ‘no’. Her hand is not scrunching the front of the horse backwards, so she has probably inherited this problem, and has to learn how to ride her way out of it.

Bearing down is the key, for it transforms the rider’s biomechanics, stabilising her torso and making her so much more powerful. (In this you use your abdominal muscles as you would when you clear your throat. Good riders do this all the time, but so not realise that they do so. They also use diaphragmatic breathing, for bearing down is impossible to sustain without this.) It may help our rider to think of being more ‘behind’ the horse. If she imagines herself as a napkin ring wrapped around a napkin, she has to (as it were) take a step back, thus putting more of the napkin in front of her. Most difficult horses want your centre of gravity in front of theirs, for they have learnt that this will make you powerless. Hence you need to keep yourself far enough back. Whizzy horses, in contrast, speed out from under you and leave your centre of gravity behind theirs, and creating the need for you to ‘keep up with them’. A small percentage of horses are ‘quick change artists’ who can change at a moment’s notice from whizzing out from under you, to slowing down and getting behind you. They require the ultimate in the ability to stabilise your torso. Think of riding in a city bus without holding on (if you have the opportunity, practice for your riding by doing so!).

The second thing that strikes me is that the horse’s head is very much to the right (i.e. to the inside) even though the rider is not pulling on the inside rein. This may also be an inherited problem, and as the horse’s nose goes to the inside his shoulders go to the outside making him ‘jack knife’ like an articulated lorry. If the rider is foolish enough to pull on the inside rein, things go from bad to worse. This horse may expect her to pull on the inside rein, and thus set her up to do so. The rider needs to think of steering the horse’s wither and not his nose, and in the ideal set-up, the horse’s front end is like a wheelbarrow. The reins are like the handles of the wheelbarrow and the hose’s nose is like the wheel of the wheelbarrow, which goes along in front of the handles. Just as you would never pull on the inside handle of a wheelbarrow (or of a bicycle) so you should never pull on the inside rein. But this is not so easy, and the rider biomechanics of good steering are hard to maintain in this kind of situation. The rider will only succeed if she has her outside aids well in place: her outside seat bone, elbow, shoulder and hand must make a wall as she thinks of bringing the horse’s outside shoulder away from the track. As soon as she advances her hand and shoulder she makes a hole in that wall that the horse’s outside shoulder can fall through. This is the kiss of death.

I saw this horse several months after this photograph was taken, and things had definitely improved. I hope that trend has continued for this rider, and made all her struggles feel worth while. A horse like this will not cut her much slack, so she will have to learn how to be both precise and powerful in her riding. I know that this is her aim, and wish her well as she learns how to translate the ideals of good rider biomechanics into practice.