RWYM

ARTICLE 21

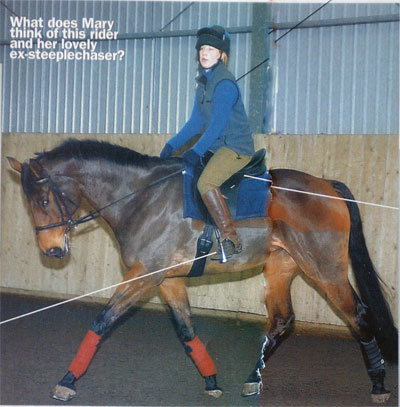

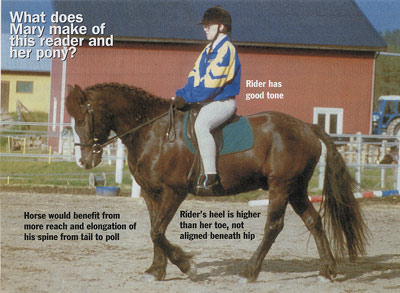

In contrast to photographs previously used in this series, this was taken at my riding centre during one of my courses. The young lad riding is 13, and the pony is a 20 year old Welsh x thoroughbred mare who belies her age. She is very forward going, jumps beautifully, and has been a fantastic teacher for Aaron, who is coming to terms with the fact that this must be his last summer on her.

In contrast to photographs previously used in this series, this was taken at my riding centre during one of my courses. The young lad riding is 13, and the pony is a 20 year old Welsh x thoroughbred mare who belies her age. She is very forward going, jumps beautifully, and has been a fantastic teacher for Aaron, who is coming to terms with the fact that this must be his last summer on her.

Aaron is pictured here in the ‘sit’ phase of rising trot on the right rein, and the camera positioning (in front of the centre point of the circle) gives us some interesting information about his rider biomechanics. Notice first that his right hand is behind his left, and that the pony’s head is facing significantly towards the inside of the circle. It is certainly not on the line of the circle’s circumference. Aaron’s inside knee and foot have come infront of their ideal line, so if we took his pony out from under him by magic he would not land on his feet on the riding arena. He would land on his backside, violating one of the most important principles of good rider biomechanics. (Given the camera angle, we can only deduce this by inspired guesswork, but I am sure this is a valid conclusion.) Also, if you look at the positioning of his head, I think you will see that it is not actually over the pony’s mane (i.e. stacked up above her midline), but is to the right (inside) of that line. So Aaron is leaning to the inside, loosing the correct positioning of his inside hand and leg, and trying to steer from his inside rein.

In reality, we have homed in on his achilles heel, for if we photographed him on the left rein we would probably find him beautifully aligned and steering well. Like all of us, he has an innate asymmetry which causes him grief on one rein. Turns and circles in canter cause even more problems than circles in trot, since increased speed magnifies the difficulty. It even affects him jumping (his passion) since if he comes at a fence off a left hand turn he will almost certainly meet it well. If he approaches it from the right rein, his asymmetry will disorganise his attempts to steer, with the likely result that he will meet the fence wrong. There is always a price to pay for those flaws in your rider biomechanics!

All of us have a tendency to lean to the inside on one rein. That lean also involves a twist which advances the outside shoulder. Conversely, any tendency to twist inwards will, on one rein at least, also result in a lean to the inside. Twisting and leaning go together, a fact well recognised by osteopaths, chiropractors, and physiotherapists – but not, it seems, by riders. It is as if the spine is a flexible mast held up by guy-ropes, and if the guy ropes do not have equal tension the mast will be pulled off vertical. On the rein where the rider’s guy ropes make her vulnerable, the forces set up by going round on a circle will pull her backside to the outside and her shoulders to the inside. (Remember the how the ‘spin’ cycle affects your washing.) This lean and twist will inevitably happen until she learns strategies to mitigate that tendency. This is one of the hardest issues to change within your rider biomechanics.

My advice to everyone is that their shoulders should stay aligned with the radius of the circle they are riding and not turn to the inside as one so commonly hears. My reasons are threefold. Firstly, any twist invites a lean. Maintaining a vertical spine and your ‘hips parallel to your horse’s hips and your shoulders parallel to his shoulders’ is virtually impossible for most of us in one direction at least. The twist in the shoulders invites the pelvis to face in the same direction, and this is much more natural to the body than maintaining a twist in the spine. This has happened to Aaron, and it has a disasterous effect on the turn.

Secondly, I have watched enough top class, international riders to be convinced that both their hips and their shoulders remain on the radius of the circle they are riding (despite the fact that this may not match what they say they do – sadly, confusions abound within this facet of rider biomechanics). Thirdly, advancing the outside shoulder causes the rider to advance the outside hand and elbow, and also the whole outside of her body including her outside seat bone. It is this that results in the pelvis facing to the inside, and it also creates a gap for the horse’s outside shoulder to dive into. He ‘jack-knives’, with his shoulders going to the outside and his nose to the inside, just as you see Aaron’s pony doing here.

Advancing the outside hand might seem like a good idea, since our instinctive logic tells us that the outside of a horse should be longer than the inside on a circle. But it virtually always causes the outside of the horse to become so much longer that he disconnects at the wither. If the rider realises that the turn is not working and pulls on the inside rein, as Aaron has done here, she reinforces that tendency. Twisting to the inside and pulling on the inside rein are the instinctive ways for riders to turn, but this ‘aid’ does not obey horse-logic.

The equivalent type of turn does not even work on a bicycle, for if you grab the inside handlebar and pull on it you will probably find yourself on the ground! However, whilst bicycle riders make that mistake only once, horse riders make it again and again. Aaron has had good tuition, has a fantastic body for riding, and also a fantastic mind which stays very focussed and calm even in difficult situations. But his instincts and his ‘guy-ropes’ still set him up to make this mistake on the right rein turns and circles. Without an effective strategy to keep him aligned and vertical, he is doomed to go wrong.

Most people who twist to the inside become heavier on their inside seat bone, and loose the outside seat bone as it advances (following the lead of their shoulders) on the turn. Aaron is one of the minority who loose the inside seat bone. It became clear to him during his lessons that he drew it up into his backside on every right turn. At the same time, he developed creases in the right side of his waistband and his chin went to the right. In effect, his body’s response to the turn was to draw his inside seat bone and his inside shoulder closer together.

The fix is a question of interrupting this sequence by finding the first domino that falls. Stop that, and you stop the knock-on effects that permeate both the rider’s and the horse’s bodies. Aaron had to think of keeping his inside seat bone down (which was easier said than done) and also of facing his shoulders to the outside whilst keeping his chin over the horse’s mane.

Like all riders, he has to think of bringing the horse’s shoulders to the inside on a turn. Thinking of steering the horse’s nose – whilst instinctive to most people – is the kiss of death. (Remember the bicycle.) He also has to think of the turn beginning from his outside aids, for his outside shoulder, elbow, hand, thigh and seat bone must make a wall which prevents the horse’s shoulders from escaping to the outside. The horse’s forehand must turn around his quarters rather as the front of a bus turns around the back of the bus, and he must be prevented from acting as if he can hinge at the wither like an articulated lorry. Once that happens, his body will follow his wither and not his nose, falling out on the circle.

It is helpful to realise that the rider who is positioned well on a turn mirrors the stance of an ice skater, who glides around to the right whilst facing her body to the left. Once she faces into the turn she looses control of it – as does the rider. Keeping the outside of the body back in place and feeling her ability to steer the horse’s wither enables her to make the turn with her inside hand still advancing. Once she looses her outside aids and feels that the turn is not working, she will panic and pull on the inside rein. This is, unfortunately, the default setting for human beings riding horses. We all resort to it when we have lost the correct (but not instinctive) positioning that works.

Aaron became able to ride the turns and circles well in trot, but still struggled in canter. However, I am sure that he has the perceptual skills and the dedication to work it out over time, and to appreciate the pay-offs he gets for developing good rider biomechanics on the turn.