RWYM

ARTICLE 22

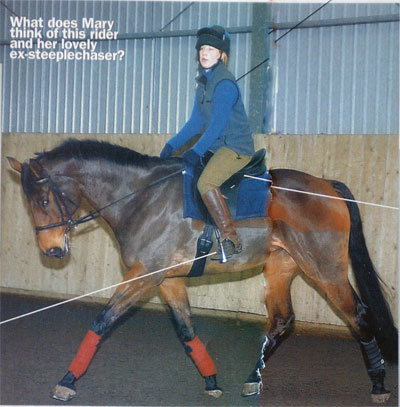

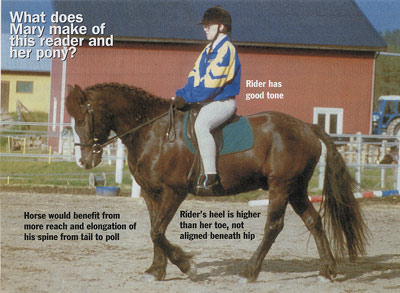

This photograph, which was again taken on a course at my riding centre, shows Helen riding Minty, her own cob who is 17 years old. She has owned him for 11 years, and has competed him in various riding club activities as well as teaching her own pupils on him. He jumps extremely well, and whilst he cannot be considered a talented dressage horse he is showing us that he too can look quite classy when he begins to reach into the rein.

This photograph, which was again taken on a course at my riding centre, shows Helen riding Minty, her own cob who is 17 years old. She has owned him for 11 years, and has competed him in various riding club activities as well as teaching her own pupils on him. He jumps extremely well, and whilst he cannot be considered a talented dressage horse he is showing us that he too can look quite classy when he begins to reach into the rein.

In terms of her rider biomechanics, Helen is doing a lot right here, and is impacting on Minty to change his natural hollow-backed carriage. He would rather have his ears much closer to her chin, and whilst more reaching has to happen for him to come truly ‘onto the bit’, he is making a significant gesture. This is much against his self-image; if he were human he would be a tear-away who did not care for the finer things in life – and dressage, for him, is a finer thing he can do without.

Helen is shown in the sit phase of rising trot, and if we took her horse out from under her by magic, she would land on the riding arena on her feet. Her foot is just a fraction too far back, with the back of her heel in line with the back of her backside, instead of the knobble of her ankle bone in line with the boney knobble at the top outside of her thigh. But this difference is not enough to destabilise her.

You can see very clearly the way that the thigh and calf form a symmetrical arrow head shape, with the knee at the point of the arrow. Notice that her stirrup length is such that her thigh bone (the mid line of her thigh) lies at about 45 degrees to the ground.This is an important tenet of rider biomechanics. Helen is not trying to ‘stetch her legs down and push her heels down’as so many people do – and even with her stirrups at the same length, thinking of this would result in her thigh being more vertical, and her foot being more forward. The arrowhead is the shape you see in the thigh and calf of riders from the Spanish Riding School, as well as in good competitive riders who naturally have good rider biomechanics. They too have their stirrups set to give these angles in the thigh and calf, and many riders are attempting to ride too long. Setting your stirrups correctly and thinking of the arrowhead can make a world of difference to your riding.

Helen’s heel is about level with her toe. Ideally, it would point down and back towards the horse’s hock – as one sees in Spanish School riders. But the positioning you see here is much better than aiming it down and forward towards the horse’s knee. When people think of pushing the heel down, the heel almost always comes in front of their backside, destroying their shoulder/hip/heel alignment. Anyone can aim their heel towards the horse’s knee, but aiming it towards the horse’s hock requires much more flexibility in the ankle joint and much longer calf muscles. It is an altogether different challenge.

Another significant point is that Helen’s foot is resting rather than pressing in the stirrup. Many people press too hard into the stirrups as they think of pushing their heels down, and by Newton’s third law of motion (which states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction) this sets up an equal and opposite push up. This upward force straightens the knee and hip joints sending the rider’s backside up out of the saddle. In terms of the rider’s biomechanics, this is obviously not a good idea! It explains why riders sit to the trot so much better without their stirrups, for with nothing to push against, this force is not instigated.

There is a very nice, stable, all-of-a-piece look to Helen’s body. I hope she will forgive me for saying that if she were a stuffed toy rider she would be very evenly and firmly stuffed. This analogy describes high muscle tone, and more commonly one sees the rider with obviously ‘unstuffed’ areas, which are the parts of the body that she cannot stabilise and control. Many riders have wobbly lower legs, or a wobbly area around their waist band, and few manage to be this well toned throughout. We all have a weakness somewhere, however, and Helen’s left side is better than her right side, which she struggles to get this well in place.

She has a very good ‘square bum’. The line of her back is close to straight, and there is a distinct corner where her backside becomes her thigh. There is also a distinct line where the outside of her thigh becomes her torso, and if you look carefully you can see a crease in her breeches at this point. This shape is not easy for most women to attain, and our backsides are much more round and spongy than men’s (one of our biggest disadvantages as riders).

Much of the work that Helen did on her course was about getting her backside more down, firm and still on the saddle. Minty has specialised in keeping her slightly up off his back, and he wants to keep his long back muscles (which run under the panels of the saddle) ‘untouchable’. Then, he can keep doing his own thing and can keep the rider’s influence minimal. The contact of our seat bones and underside with the horse’s long back muscles creates our primary connection with him, and I love the analogy of ‘plugging in’ to him. It really is as if our seat bones had little extensions, like those plastic cowboys and indians that ‘plug in’ to their plastic horses.

Think of trying to put an electric plug into a socket in the dark. The pins would move backwards and forwards over the holes until ‘glunk’, the connection is made. Plugging in connects the rider to the horse’s brain, body, and energy system, but most riders have so much movement in their seat bones that this connection is never made. Helen learnt to make it on a deeper, more effective level than described here, but in your initial experiments think of halving the movement in each seat bone. Then halve it again, and think of reducing each seat bone movement down to one quarter of an inch.

Your aim is to have no extraneous movement over and above the movement that moulds you onto the horse’s long back muscles – and these move much less than most riders imagine. This extraneous movement would ‘unplug’ you, allowing the horse to dictate the way those muscles move and the speed at which his legs move. Your rider biomechanics are then far less effective as the horse becomes the one who moves you, instead of you being the one who moves him. When the rider is the ‘prime mover’ she has far more stability and control. This is marks the point at which riding can become dressage.

The least stuffed part of Helen’s body is her arms. The good news is that there is a corresponding lack of tension in them, and a very nice line from the elbow via the lower arm and rein to the horse’s mouth. Helen has not restricted Minty’s reach into the rein. But the bad news is that her hand has given forward just enough to ‘take the lid off the end of the toothpaste tube’. There is almost a loop in the rein, and her elbows have come too much in front of her torso. Her armpits needed to be kept more closed at the back, with just a little more tone in her arms, and her fingers slightly more closed around the reins.

There is a very delicate line between not giving the hand enough, and giving it too much. With no lid on, the horse has more options, and an untrained horse will often momentarily reach into the rein and then retract his neck again, coming above the bit. To become secure in this reach, he needs to be reaching into a more secure contact.

However, in bringing the horse into carriage, the role of the hand is secondary to the role of the rider’s abdominal mucles. The golden ruleof rider biomechanics is that the rider’s bear down (the push of her guts against her skin, which we naturally do when we clear our throats, and which good riders do all the time) must be stronger than her hold on the rein. This is definitely true in Helen’s case, and she has the abdominal strength of a good rider. But she also needs to ‘keep the lid on’, so that more stuffing builds up in Minty’s neck, making it reach and arch more up above the rein, putting him that bit more ‘on the bit’.

This paradox is not easy for most riders. They bear down, and give the hand too forward, or they bring their hand back and at the same time they bring their stomach back, sucking it in. It is a delicate matter to use the power of your bear down to push the horse’s neck away from you, whilst keeping the ‘lid on the end of the toothpaste tube’. But your horse will repay you handsomely when you manage it, and it only needs you to become consistent for him to become consistent as well, so that your good rider biomechanics generate good posture and movement in him.