RWYM

about us

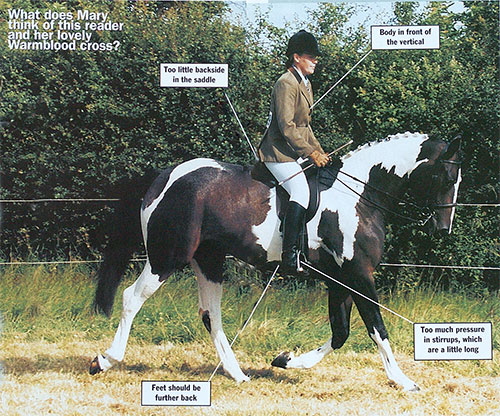

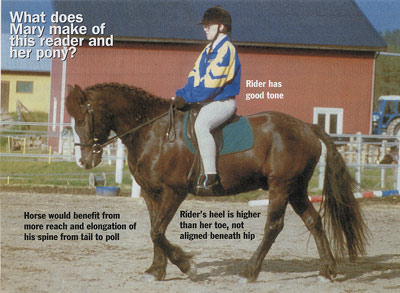

The photograph shows a six year old Hanoverian mare, who has been owned by her rider since she was three. I saw her in the flesh at one of my lecture demonstrations earlier this year, and she is indeed an impressive horse. Despite getting nervous at shows, she has had some success in affiliated novice competitions. Her rider, however, feels that she is letting the horse down, and says, ‘Her big movement makes it difficult for me to sit back and not tilt forward. I would love to learn to relax and use my whole body more effectively.’ Good rider biomechanics, however, may not lie in relaxation.

The photograph shows a six year old Hanoverian mare, who has been owned by her rider since she was three. I saw her in the flesh at one of my lecture demonstrations earlier this year, and she is indeed an impressive horse. Despite getting nervous at shows, she has had some success in affiliated novice competitions. Her rider, however, feels that she is letting the horse down, and says, ‘Her big movement makes it difficult for me to sit back and not tilt forward. I would love to learn to relax and use my whole body more effectively.’ Good rider biomechanics, however, may not lie in relaxation.

In this photograph, the rider’s upper body is actually vertical, with her shoulder seam directly above the boney knobble on the outside of the thigh where it joins the pelvis. (If you don’t believe me, place a piece of card along that line.) The shape of her blouse is deceptive, making it difficult to judge the shape of her back, but it appears slightly rounded, with her seat bones pointing forward and her front caved in. But this is not the same as leaning forward. When I met her a few months after later she had made a correction but overdone it, and was leaning back, lifting her chest, and hollowing her back. She had gone from one version of disorganised rider biomechanics to the other!

From the beginning point that we see here, what she really needed to do was to check that her seat bones were pointing down, and that she had a straight vertical line from her pubic bone to her belly button to her sternum and her collar bone. Then she needed to close her armpits at the back instead of the front. These two corrections of rider biomechanics are tremendously powerful for anyone with a tendency to round their back, and they inherently guard against over-kill. With a flatter back and a more obvious chest, our rider would have a more elegant position, which would then need the addition of more power. But to exaggeratedly lift her chest and lean back created a different set of problems.

I suspect that her fear of leaning forward may be just that – a fear that does not manifest in reality, and that her perception of how she rides might well be out of date. Teachers often point out an apparently incessant fault, leaving the rider convinced that this is her problem. So when she finally fixes it she remains in blissful ignorance of her achievement, and promptly continues to over-correct! This happens particularly in relation to leaning forward or back, and being round backed or hollow backed.

When our self-image is out of touch with reality it can become quite confusing to be presented with the truth. A mirror or a video camera will make the point very clearly, but will still leave the rider dazed and phased by this new information. I like to send riders away from my courses, for instance, knowing where vertical is, and having overcome the shock of finding it. But if they had to make a correction to get themselves there, the chances are that some (the more zealous, determined ones) will over-correct, and some (the more laid-back and lacking in focus) will loose the correction.

One of the worst design faults in the human body is, in my opinion, the lack of a built in spirit level! So without ongoing visual feedback, we are swearing blind when we insist that we are vertical (or forward, or back), and few people appreciate the degree to which our feel sense cannot be trusted. Any new feeling will soon begin to feel less profound than it did at first, and this should leave you asking yourself whether you are habituating to the feeling, or whether you are no longer doing it enough. You can only create the feeling with equal intensity by making the correction more and more profoundly, with the result that you soon over-correct. This means that with all the best will in the world, we easily loose the plot. This is one of the more confusing aspects of learning good rider biomechanics.

Let’s come back to our rider. Whilst her back is not ideally aligned, her foot is a long way in front of the correct shoulder/hip/heel vertical line.(Use your piece of card again.) I well believe her when she says that she struggles to stay ‘with’ this horse, and the acid question is, ‘What would happen to her if we cut the reins?’ I am not convinced that she would stay in place, and the look of the arm and wrist in particular make me think that she needs the reins as a counter-balance. She is dangerously close to ‘water-skiing’ – the fate of any rider who does not have enough power in her body to match the power of the horse’s step.

If you are riding sitting trot on the lunge and holding on to the front of the saddle, it is relatively easy to stay in place. But once you let go, you are highly likely to bump backwards. This leads me to conclude that a force is required to hold the rider up to the front of the saddle. Essentially you have two choices. One is to provide a force with the hand and arm that acts from the front towards the back, and the rider holding the front of the saddle has been given permission to do this, whilst the rider holding the reins has not. The other choice is to provide a force within the body itself which acts from the back towards the front. Only this keeps the rider ‘with’ the horse in every bound that he makes. It means that she can ride along saying ‘Look, no hands’.

Our rider needs more of this force. But she, like many others, is convinced that she will stay ‘with’ the horse better if she relaxes more. Teachers may well have made her aware of the tension in her arms and hands, and here she does indeed need to let go. But this does not mean that the whole of her should relax – this is a misunderstanding of rider biomechanics. The tension in her arms is only there because they are attempting to make up for what her torso is not doing. i.e. the pull back is a compensation for the lack of push forward. The torso needs more stability and tone, and along with this, her joints need to function as more effective shock absorbers.

Sit on a chair in as close to an ‘on horse’ position as you can manage, making sure that you are vertical, with your seat bones pointing down. Then have a friend try to push you off balance. She can push on your upper chest, your back, and the outsides of your arms, as well as on the sides of your waist. She needs to be gentle and respectful in this, gradually increasing the intensity of each push. As you find ways to stabilise your body, you are discovering the muscle-use you need on your horse. You will probably find yourself bearing down, using your abdominal muscles as you would if you coughed or cleared your throat. This is a key to the stability and effectiveness of good riders.

You will certainly not succeed in staying stable if you think of yourself as a rag doll (most people’s interpretation of ‘relax’). This is a far cry from bearing down, and most riders are shocked when they realise how much muscle power it takes to make a push forward with your abdominal muscles which is stronger than your hold in the rein. Only then are you riding the horse ‘from back to front’ instead of ‘from front to back’. If you still have a ‘space hopper’ left over from childhood, blow it up and hop about (with only a loose hold on the handles). Realise how much effort it takes. Whilst a skilled rider looks as if she is doing nothing – and may even tell you that she’s doing nothing – this is really an optical illusion. To create the stability and stillness that are the essence of good rider biomechanics, her core muscle are working their socks off.

Looking at this rider, one cannot easily impose a stick figure on her body. Think of the riders of the Spanish Riding School, where one very easily can. Their joints form clear angles. The stick figure test sounds too simplistic to be useful, but it is actually a very good indication of the way in which the joints work within good rider biomechanics. Think of one of those wooden puppets, with a little metal ring for the ankle, knee and hip, and the wrist, elbow, and shoulder. The parts between the joints are solid, but the joints give. The rider who tries to relax becomes like a bendy-doll that gives everywhere – the bits between the joints are soggy, and the joints themselves do not have such a clear-cut function. In fact, they often hold tightly to protect a body which inherently knows it is unsafe.

To progress up through the competition grades, and to feel ‘at one’ with her horse, our rider needs to find the power of bearing down. A Pilates class would well help her to build the right strength, but she may need a riding teacher to help her apply it. She is right that her horse (like every horse) deserves her best riding. With a fair few pieces missing from the puzzle she can make it look pretty good – just think how good it could be when her rider biomechanics are more correct. Only when you are ‘with’ your horse, can you say it in ‘horse’, and allow your horse to move without constriction. It is easier said than done, but a very worthwhile challenge.