RWYM

ARTICLE 28

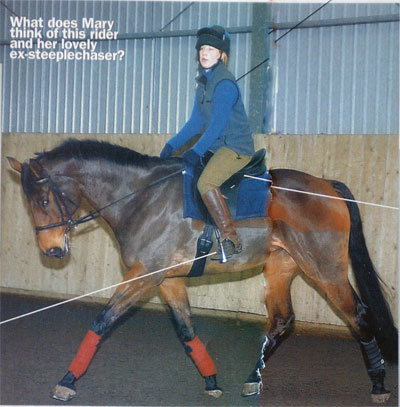

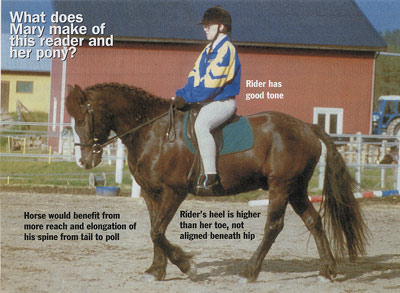

The photograph shows a 9 year old thoroughbred, who has been owned by his present rider for just over a year. He previously had three eventing homes in three years, and it seems as if some promising early results led to him being over-faced and loosing his confidence. He is an unusually nice thoroughbred, with three good paces and a willing attitude, so he was bought with full knowledge of his past and as a potential dressage horse. His owner hopes to build on her successes in affiliated preliminary and novice tests, and to work her way up through the competition grades.

The photograph shows a 9 year old thoroughbred, who has been owned by his present rider for just over a year. He previously had three eventing homes in three years, and it seems as if some promising early results led to him being over-faced and loosing his confidence. He is an unusually nice thoroughbred, with three good paces and a willing attitude, so he was bought with full knowledge of his past and as a potential dressage horse. His owner hopes to build on her successes in affiliated preliminary and novice tests, and to work her way up through the competition grades.

The photograph shows work that is very nearly very good, but even though the rider is doing a lot right within her rider biomechanics, she does not look as if she is really at ease and in charge of the situation. Her line up and the angles of her joints are quite good, but she is not part of the horse – she looks rather perched on top of him, and I have a horrible feeling that she may not be breathing very deeply. In fact, soon after writing this I spoke to her on the telephone and discovered just how right my assessment was. For the photograph was taken about ten minutes into her competition warm up, and very soon after a high-spirited buck had nearly decked her!

The rider considers herself a nervous character, whose inability to relax affects her horse. We all know from experience that whenever we become somewhat unnerved we instinctively tend to back off and become tentative – except, of course, for the hand, which becomes stronger. It is easy to know, intellectually, that using the ‘hand brake’ on an explosive horse can lead to even more dire explosions. But theory and practice are two different things, and there is definitely some ‘handbrake’ tension in this rider’s lower arm and wrist.

Riders basically come in two kinds. There are the ‘control freaks’, who really like to know that they are in charge, and there are the ‘thrill seekers’ who are happy to go along for the ride even when they aren’t. In fact, they find school work boring because they do not notice the subtle distinctions of ‘getting it’ and ‘loosing it’ that make it fascinating and fun to discover how good rider biomechanics influence the horse. Without this, round and round in endless circles can be like watching paint dry. Speed and the thrill of the chase are what make it fun for them, and subtle control is for wimps.

Meanwhile, anyone with ‘wimp’ tendencies somehow has to find the mind-over-matter determination to get the horse’s attention, even and especially in those explosive situations. The rider needs to use her lower leg, and to kick hard if necessary, saying ‘Hey you, listen to me!’ In the photograph, this horse’s ears are pricked, and he looks much more interested in the view than he is in his rider. This is a dangerous way for him to be, and the rider needs to make herself more compelling to him than the outside world. Once his brain is tuned in to her, his ears will come out sideways. This means that every time he pricks them, she must kick.

A ‘thrill seeker’ would have much less problem in riding the potentially explosive horse forward. It would be instinctive for her to channel his energy instead of damming it up, over-using the hand in a misguided attempt to get control. But for a ‘control freak’, the change from stopping him with the hand to sending him forward with the leg is a significant act of courage – and it is not quite the same as relaxing! The arm might need to relax more, but the body needs to firm up and ‘go for it’ whilst obeying the rules of good rider biomechanics.

I am not going to pretend that overcoming those fear-driven, hand-dominant instincts is easy. But there are other aspects to this, and they provide is the key that makes it possible. Firstly, the rider needs to be in control of the speed at which the horse moves his legs (the tempo) and secondly, she needs to have enough power in her body to match the forces that act on her torso in every step the horse takes. In this case, on a scopey, forward-going horse, those are big forces. Hence the need to ‘go for it’.

I make a distinction between whether ‘you take the horse’ or ‘the horse takes you’. Think of riding a bicycle. Whilst you are pushing the pedals around, you take the bicycle, but as soon as you reach a steep down hill, you find that you cannot pedal fast enough to keep up, and then the bicycle takes you. When the horse is taking you, he is in control of the speed at which he moves his legs, and it can feel all but impossible to lighten your hand and use your leg – even when you know, intellectually, that pulling on the reins will not slow his legs down.

Gaining control of the speed at which the horse moves his legs requires the rider to make her body into a metronome which says, ‘1-2-1-2-1-2. I will only allow you to move in this rhythm’. She does this by making a pause in the air at the top of the rise, and a pause in the saddle as she lands.This is an important skill to learn as you develop your rider biomechanics. This approach usually works better than thinking of moving slower on the way up and slower on the way down.

If you feel as if you land in the saddle only to have the horse catapult you out of it, he has made you all but powerless. This will undoubtedly happen if your seat bones are pointing backwards as you land, and it is one of the knock-on effects of hollowing your back.

If we were seeing our rider directly from the side, we would see some of the pointers of a good alignment, and these suggest to me that even though her arm has reacted badly to her fright, her body has not reacted as badly as it might have done. She has a good arrowhead shape to her thigh and calf, with the knee at the point of the arrow. Her thigh bone is at about forty five degrees to the ground, and her heel is well positioned under her hip, and is level with her toe, with the foot resting rather than pressing into the stirrup. The heel does not need to be down until you are jumping, when a lowered heel can save your life.

She has hollowed her back somewhat, but not to the extremes that one often sees, and she has not made a couple of other mistakes that go with thsi, and that make your rider biomechanivss much less effective. The first is growing up tall, sucking your stomach in, and pulling your ribs up away from your hips. The second is stretching your legs down and pushing hard into the stirrups. Elongating your body like this not only makes you hollow your back (try it), it also restricts your breathing to your upper chest. Also, pushing down into the stirrup generates (by Newton’s third law of motion) and equal and opposite force that straightens your knee and hip joints, and sends your backside up and out of the saddle.

Since I am cautioning you against growing up tall and stretching your leg down (especially in those tricky situations), why are riders are taught to do this? I believe that those words are meant to describe a completely different feelingof good rider biomechanics that advanced riders get when they are riding well. Mistakes become perpetuated because teachers usually repeat without question what their teacher said, and what they have been told to say, and they rarely attempt to work out for themselves what really works.

So for our rider (and you) to feel safer when faced with the threat of an equine explosion, my first suggestion is BREATHE. Breathe in deeply, attempting to feel as if the air goes all the way down to your abdomen. Be sure to breathe out again. Keep your ribs down towards your hips and your feet resting lightly in the stirrups. Do your utmost not to resort to the ‘handbrake’, but seek the courage to use your lower leg. Think of using it to get the horse’s attention, and of channeling his energy to your ends. Realise how much safer you are when 80% of the horse’s brain is listening to you and doing your bidding. And if you only have access to 20% of his brain, the other 80% can do precisely what it wants – and if you back off and ride only with your hand, that 80% has too many options.

Remaining proactive with your leg and your body is much more possible when you are in control of the tempo. So you have to be brave about being a metronome – thrusting your pelvis forward over the pommel as you rise, and landing in the saddle with your seat bones pointing down as you sit. This enables you to get a pause in the saddle as you land, so that you ‘take the horse’. If you find yourself hovering out of the saddle half way between the rise and the sit, or frozen into a ‘foetal crouch’, you have really ‘lost it’, and do not have the skills to be in that situation.

Finally, all of the above becomes much more possible when you are bearing down. This use of the abdominal muscles is the key to forward, effective riding (even and especially when the chips are down). The ‘thrill seekers’ would be doing this without even knowing they were doing it, for it is an inherent part of confidence. You push your guts against your skin just as you do when you clear your throat, cough, or giggle. It is that simple – and that hard – to become more brave and powerfu, with goodl rider biomechanics.