RWYM

ARTICLE 30

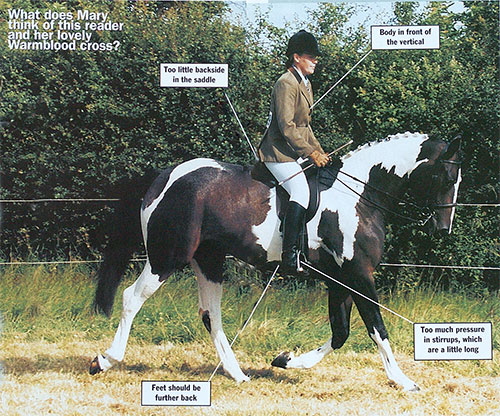

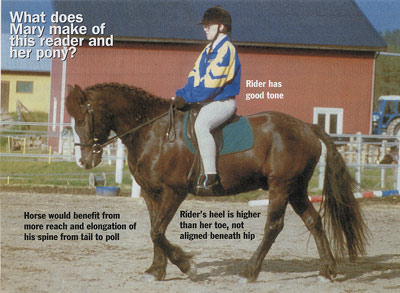

This photograph shows a 17hand nine year old Irish Draft/Thoroughbred mare who has done all riding club activities as well as affiliated Pre-novice eventing. She is a very genuine and easy-going soul, and it may come as a surprise to anyone looking at this photograph to know that she is actually very long backed. That she looks so in proportion here is a tribute to how well she is being ridden by someone who is a BHS qualified Intermediate teacher and a senior coach within my network.

This photograph shows a 17hand nine year old Irish Draft/Thoroughbred mare who has done all riding club activities as well as affiliated Pre-novice eventing. She is a very genuine and easy-going soul, and it may come as a surprise to anyone looking at this photograph to know that she is actually very long backed. That she looks so in proportion here is a tribute to how well she is being ridden by someone who is a BHS qualified Intermediate teacher and a senior coach within my network.

The horse needs to be just a fraction more out on the end of the rein, putting her nose on instead of a little behind vertical. But there is a very good ‘power lift’ to her movement. This term was coined by an artist friend of mine, who knew little of the technicalities of dressage, but who could draw that quality with just a few strokes of a crayon. There is a lovely connection along the mare’s top line, all the way from her tail to her poll, as if the whole of the rest of her body were hung from that line. This gives her the ability to move her limbs very freely, and instead of plonking down heavily onto the ground, she appears more weightless than she is.

A colleague of mine who is a senior figure in the judges training programme in America tells the story of attempting to start a discussion amongst the trainers about ‘throughness’. She felt that they needed better ways of describing it, and teaching their trainees to see it well. Everyone was so stumped for words, however, that the discussion fell rather flat. So that evening she cornered her roommate, and refused to give up until she came up with a good description. ‘Well’, said her colleague (after much sighing and head scratching), ‘it’s as if there’s a line of dominoes all along the horse’s back and crest, and all the dominoes must be pointing forward. As soon as one of them isn’t, the horse is not through.’

My friend cracked up with laughter at the originality of this description, and how effectively it does indeed describe ‘throughness’. But her colleague was disturbed by her laughter. ‘What’s so funny’, she said, ‘doesn’t everyone see it like that?’

Thinking in mages like this gives us great scope for ingenuity, and often says it far better than literal descriptions. I love the idea, for instance, of the horse moving on round wheels instead of square ones. (The horse in the picture would definitely have round wheels.) This idea was coined by the husband of a client of mine, who saw with innocent eyes the changes in his wife’s horse.

I also like to think of the muscle chain from each of the horse’s hind legs to his poll like a pair of hosepipes, running just to each side of his spine and crest. Sometimes those hosepipes are full of the kind of debris that might accumulate over a winter, and the water has to power through them with enough force to clear the blockages away. Also, the rider must not land on those hosepipes with so much force that she blocks the water flow. The saddle too must not constrict them. And the water must flow as a constant stream – not in the kind of spurts that can happen after an air lock. And this, in turn, could make the horse look like he has square wheels, or as if he has the kind of ‘kangaroo petrol’ that can make your car splutter and lurch as you start it on a cold morning….

Without images, my teaching would loose an awful lot of its impact and its clarity. This is the language that appeals to the right brain hemisphere, which thinks in picture and ‘feelages’ rather than words. So the words satisfy the left (literal, language) brain whilst the picture speaks to the right, and with both sides of your brain engaged in the action, you take in far more than you would if I remained literal. An anatomy lesson about the muscles of the horse’s top line and the biomechanics of his movement might well have its place, but you would find it rather dull, and easy to forget. And since it is the right brain hemisphere that does the riding, this theoretical knowledge will leave you no better off…

This is why reading books about riding does not make you a better rider. Your left brain can recite the theory, but your right brain has still not ‘got it’. We all ‘get it’ in stages, especially when our starting point is not that great. The rider in the photograph has got many facets of riding working really well – so well that she has been able to bring this horse into a really nice carriage by the use of her torso and thigh. She has not resorted to ‘kick and pull’, which can never yield this degree of ‘through’, ‘reaching’ and ‘unscrunched’.

Her hands, for instance, are clearly out in front of her (as if she were pushing a baby buggy) and are not pulling back. She is slightly on tiptoe, and it would be better to see her heel level with her toe if not slightly down. Leveling out her foot would bring her knee slightly further down and back on the saddle, which would give a more classical look.

Overall, the angles of her body are good enough, and at this phase of the stride in rising trot one would expect to see her body inclined slightly forward. She would land on the riding arena on her feet if we took the horse out from under her by magic, but she might then wobble a bit. Change the knee and foot slightly and she would be secure.

The biggest change she needs to make, however, concerns the ‘A frame’ made by her thighs. This is too tight at her knee, and not narrow enough at the top of the thigh and across her back. The extreme of ‘grip with your knees’ can make the rider look as if she would ‘ping’ backwards off the horse like a clothes peg. But the converse of ‘relax your knee, take your thigh off the saddle’ never gets hold of the horse’s rib cage enough to draw it upwards into the carriage you see here. Although it is often said, it is not what really good riders do.

The rider literally does hold the horse in an ‘A’ frame. This is a more profound concept than you might realise as you read these words, and it gives the rider an even contact down the inside of the thigh from the tendons at the corner of the pubic bone down to the knee. I like the idea of the thigh being ‘snug’ against the saddle, although many people who have ridden with their thighs off the saddle make this change and tell me that they feel as if they are gripping. Remember to notice this next time you ride, and compare yourself to the ‘A’ frame ideal.

The ‘A’ frame too must be in the right place, and it is the need to get the horse ‘in front of her’ that has caused this rider to over-emphasise the contact in the lower thigh and knee. This horse could easily look as if there were more horse behind the rider than there is in front of her, and it can help the rider to think of herself like a napkin ring around a napkin. If the napkin ring can, as it were, take a step back around the napkin, more napkin is then in front of it. The horse’s shoulders and neck can then reach out infront of the rider, and can fill up with ‘stuffing’ (as they would in a brand new stuffed toy horse).

This idea is especially helpful on backward thinking horses, who effectively keep saying ‘you go first… after you,’. Some can even feel as if they are trying to crawl out backwards from under you, and their attempts to not go can leave you feeling powerless as you flounder about on their neck. Nothing you do will work until you get your centre of gravity back over theirs, and to do so you must reinstate your ‘A’ frame and bring it far enough back on the horse’s torso.

In keeping her ‘A’ frame back enough, this rider has made its arms are too parallel, but despite making this mistake she is having a very good effect on the horse. If she could close the ‘A’ frame behind her and begin her bear down in her back (which I do not have the space to explain to you now) she would be in a super place.