RWYM

ARTICLE 4

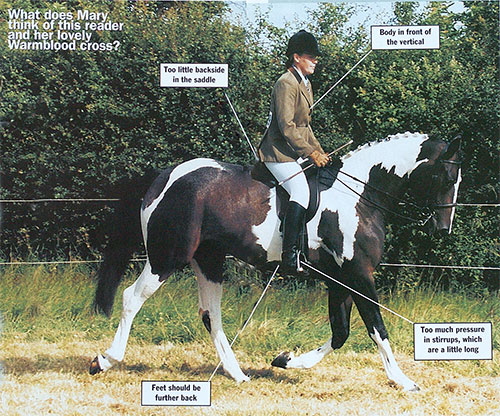

This young lad is riding an attractive little mare, who is five years old, and who has done well in coloured horse show classes and in novice jumping.

This young lad is riding an attractive little mare, who is five years old, and who has done well in coloured horse show classes and in novice jumping.

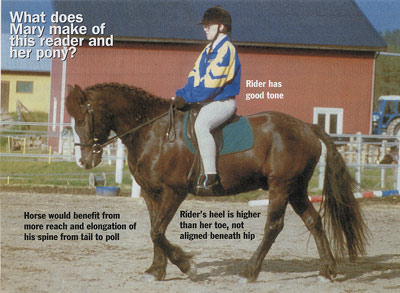

As in the majority of photographs, some things are working well, and others less so. At this phase in the trot stride, it is difficult to assess if the horse is tracking up, so we cannot comment on her activity. The line of her back and neck look good at first glance, but she is not ‘on the bit’ in the way one would like to see. There are two key issues which are limiting her ‘throughness’.

The first relates to the rider’s body use, and I have concerns about his hand, and the degree to which he is riding the horse ‘from front to back’ instead of ‘from back to front’. How much is he thinking about bringing her head down, and how much is he thinking about bringing her back up? I suspect that he has been told not to pull, and that he is trying to be obedient. But at the same time he is desperate to keep the horse’s head down – so he has developed the cunning idea of rounding his wrists to make a covert pull. The horse does not look happy in her mouth, and I suspect that if he straightened out his wrists (so that the back of his hand became a sraight-on continuation of his arm, with the thumb on the top of the rein) his worst fears would materialise. If he were to advance his hand and lighten the contact, her nose would almost certainly go up in the air!

Making the change from bringing the horse’s head down to bringing the back up is the hardest task that faces many riders. The hand will always (unconsciously, and as if it had a life of its own) attempt to make up for what the body is not doing. What happens in the hand is thus a symptom, and teachers make little progress with ‘bad hands’ until they address the cause of the problem. Instead of saying, ‘Don’t pull’ (or variations on that theme) they have to give the rider something else to do instead. That ‘something else’ involves the torso. However, the rider must somehow be persuaded to use mind-over-matter to inhibit her panic reactions, giving herself the time to substitute more correct responses which are aimed at influencing the horse’s back instead of his head.

Our rider is limiting his effectiveness by leaning forward. This may be an in-the-moment response which is symtomatic of his fears, and many riders panic as soon as the horse threatens to lift his head, tipping forward and becoming hand-dominant. But it could just be that he is riding with his stirrups too short, and is, on a perminant basis, vereing towards jumping position. We cannot know if he is in fact about to jump, if he thinks this is the right length for his stirrups, if he is attempting to fit his long legs around this rather small horse, or if he has grown without realising it. (This is a common reason why both children and adolescents ride too short, although in general, the vast majority of would-be dressage riders have their stirrups too long.)

In flatwork the thigh bone should lie at 45 degrees to the ground, or slightly more vertical. His is too horizontal and he needs to put his stirrups down at least one hole. However, there is a nice line to the thigh and calf: they make a good arrowhead shape, and they have naturally high muscle tone. They look as if they have solid bones inside them and are not just made of mush. To use another analogy, the rider looks like a brand new stuffed toy rider, and not like an elderly one who has seen better days. These are more like Superman’s legs than Clark’s legs.

If the rider’s worst fears came true and the horse did raise her head, she would, to use my favourite terminology, push back at the rider. It is as if someone put their hand on her muzzle, pushing her muzzle back into her poll, her poll back into her neck, her neck back into her wither, and her wither back into her back. This then drops, forming the hollow which I call the ‘man-trap’. Once the rider’s body weight falls back down that hollow, she perpetuates it. So whenever you make the mistake of treating the horse like an armchair – riding like a sack of potatoes and relying on him to hold you up – you encourage him to either become or remain hollow.

The trick is to keep supporting your own body weight, using the thigh as part of the sitting surface, so that it works as a lever (hence the importance of having the thigh bone at 45 degrees to the ground.) Our rider is doing this quite well. The problems here lie more in his upper body than in his leg, for this is not Superman’s torso. It is both tipped forward and lacking in tone. The key issue is that by tipping forward the rider is limiting his ability to push the horse’s neck away from him. To succeed in this he has to generate a force in the forward direction which is bigger than the horse’s push back.

It is the muscle use which I call bearing down that will come to his rescue. You do this naturally when you clear your throat, cough or giggle (try it). It is as if you push your guts against the wall of your skin, and as you do this when riding, you think of pushing the horse’s neck away from you. The use of latisimuss dorsi (a large muscle in the back) which I explained in last month’s article would make this ‘push’ even stronger. The way that it works can seem like a miracle; but if you are tipping forward, lowering your hand, and panicing about the horse’s head position, your wrong reactions prohibit you from making the right reactions. And because your panic-based reactions are doomed to fail, you often create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Your worst fears are likely to become reality, making you panic even more next time.

The second issue here is much more subtle, and requires a far more refined level of awareness to perceive and correct. You may have to look very carefully at the photograph to appreciate that the horse is tilting her muzzle, so that her nostrils would come out of the paper towards us. If we could get a circular saw and begin cutting up between her forelegs and along the underside of her neck (God forbid), the saw should come out along the line of her crest and the centre line of her nose. The rider’s spine should also lie on that same axis. But the horse’s neck and shoulder girdle are twisted off that axis, making her left ear lower than the right.

Many riders attempt to correct this by lifting the hand on the side of the lower ear. Although this makes instinctive sense, in my experience it does not work, especially in the longer term. Much more of the horse’s body is involved in this evasive pattern than just the head and neck, and when the pattern operates, it is as if the horse is making a twist in his entire spinal column, mirroring the way that you would wring out a dish cloth.

So when I see this happening, I ask the rider if she can detect any difference in the height of the two long back muscles which lie beneath the panels of the saddle. The one on the side of the lower ear will be lower. (To understand this, imagin that you are the horse; lean forward as if your back was his back, and twist your ‘muzzle’ to the right.) The rider may also be able to detect that the horse’s pelvis is twisted, with the point of the hip being lower on that same side. If you imagin sitting astride a table top, it could even feel as if one back leg of the table were shorter (in this case the left), creating a tilted surface. I believe that the tilt in the horse’s body always extends back beyond the neck, even though an unsophisticated rider may not be able to detect this. I also believe that the secret of success with this evasive pattern lies in leveling out the two sides of the back. The lower side (the left in this case) needs to be drawn up under the rider’s seat.

This is a very subtle correction, and head tilts have been the bane of many good riders. But once you know how to use you thighs as levers so that your body can function as a suction device, it is not so difficult to level out the back. Keeping it level throughout all the gaits and all the movements might, however, be extremely challenging! It pays as you do this to keep thinking about that circular saw axis, making sure that you yourself are not contributing to the problem by loosing your correct axis.

This correction is probably beyond our rider’s ability at the moment – it lies in a deeper layer of the onion than he is currently able to work with. His big challenge is to quit worrying about his horse’s head position, and to develop trust in his body as the tool which can solve the problem of hollowness. He will only develop the correct reflexes when he thinks more about the horse’s back and the base of her neck than he does about her head position. But to do this he has to work his way out of the most difficult catch 22: until he experiences that bearing down can work for him, he will not trust that it can. But until he trusts that it can, he will not experience it working for him.