RWYM

ARTICLE 5

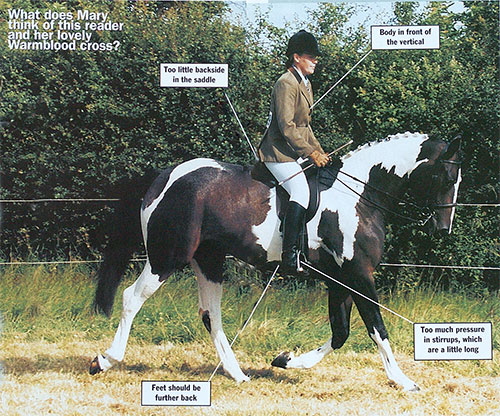

This horse, who bears the apt name of Paddy McDuff, is a 14.3hh Irish Draft x Conemmara gelding. His rider bought him at four, after he had been backed in Ireland and hunted lightly. She tells me that he was then very ‘upside down’, but that over the last three years his general shape has changed. He is a short coupled horse, with long strides – his rider describes him as ‘a small horse and not a large pony’ – but she has not been able to get him to stretch his neck and lengthen his stride further. She competes in everything from Handy Horse to showjumping and dressage, where her test sheets repeatedly say ‘would improve if he could lengthen his neck’.

This horse, who bears the apt name of Paddy McDuff, is a 14.3hh Irish Draft x Conemmara gelding. His rider bought him at four, after he had been backed in Ireland and hunted lightly. She tells me that he was then very ‘upside down’, but that over the last three years his general shape has changed. He is a short coupled horse, with long strides – his rider describes him as ‘a small horse and not a large pony’ – but she has not been able to get him to stretch his neck and lengthen his stride further. She competes in everything from Handy Horse to showjumping and dressage, where her test sheets repeatedly say ‘would improve if he could lengthen his neck’.

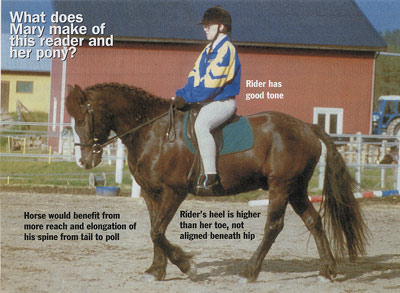

Paddy is certainly a very handsome chap, who looks to be in wonderful condition. He is shown here in canter right, with the left hind weight-bearing. But the first thing that strikes me when I look at the picture is that if he wanted to lengthen his neck he probably couldn’t, as the length of the reins would prohibit him. I suspect that the rider has taken up the reins in a neck-scrunching way.

Her balance on him is pretty good, although you could criticise her toe being rotated out and her heel being rotated in. I suspect that this is not a momentary problem, but a way in which she clings onto him with her lower legs. If you look carefully, you can see that she has made a crease in the saddle flap behind her knee. In general people are far more inclined to do this in canter than in trot (perhaps it is in canter that desperation strikes), and instinctive though it is, it does not help. This rider would benefit from thinking of rotating her toes towards the horse’s elbows and her heels away from his sides. Her leg aids need to function as a momentary slap, and after them she needs to be sure that she returns to this position.

Her stirrups are on the short side, for her thigh is probably more horizontal than the ideal of 45 degrees to the ground. She may be warming up for a working hunter competition and thus have her stirrups set for jumping; if not, she needs to go down a hole. Notice that the front line of her saddle flap is vertical, and that she barely has enough room in the saddle to accommodate the length from the back of her backside to her knee. This will be alleviated slightly by dropping her stirrups that hole (although she will then need to make sure that she keeps her knee in its new place on the saddle, lower down and further back than it is here). But I fear that the saddle will still not fit her well. Ideally the flap should have a slight forward curve, and the seat may need to be longer.

Her position as seen on the outside of the turn is interesting. Her visible hand on the outside of the circle has probably given forward too much. Her inside hand, which you can just see (along with the head of her whip), is carried lower down and is well behind her inside hand. The fact that we see so much of her back suggests that her whole body – both pelvis and shoulders – may be twisted to the inside. She has made what I call a ‘handlebar turn’, analogous to pulling on the inside handlebar of a bicycle.

The most effective way to turn keeps the rider’s outside shoulder and outside seat bone back. She then remains in what I call ‘fencing lunge position’. This mirrors the way in which an ice skater goes round a curve, gliding on her inside foot with her body facing outwards. The moment she twists her body in she looses control of the turn and spirals out of it. So it is with riders and their horses.

Let’s come back to the more pressing issue of lengthening the horse’s neck. Short-coupled horses often scrunch themselves into little balls, and the neck will not lengthen unless the back also lengthens. This requires the rider to lengthen the distance from her knee to her seat bones. It is as if she puts both herself and her horse on the rack – the medieval torture instrument that stretched the poor victim until he confessed his crime. In effect you elongate your thighs, and as you do so you elongate the horse underneath you. Doing a good job can hurt your thigh muscles so much that the rack can seem like an apt image!

Try this exercise sitting on a hard chair. Sit with your thighs horizontal, together, and at 45 degrees to the front of the chair. Keep both seat bones on the chair with one of them close to its front edge, and be sure that they are both pointing down. Place your fingers an inch or two in front of the knee that is furthest away from the chair. Now reach your knee to touch your fingers. Back your knee away from your fingers, and repeat this several times, realising that your knee can move by probably over two inches. Feel how your seat bone rolls back and forth over your flesh, but keeps pointing down. Finally, reach your knee to touch your fingers and keep it there whilst you think of elongating your thigh in the backwards direction as well. It is as if you push back off your knee and slide your seat bone back over your flesh. If you sit like this for a while you should feel a profound stretch along the top of your thigh. Repeat the exercise with the other thigh, and notice any differences between the two sides.

I teach this on horseback by diving down under the horse’s neck, grabbing the rider’s knees and pulling on them. I then instruct her to draw her pelvis back away from her knees, and I ask someone to watch from the side to be sure that she does not lean back or hollow her back. It is as if the rider’s thighs are the elastic in a catapult, and she may feel the stretch along the top of her thigh, or along its inside, underneath, or outside. Any of these is fine, and serves as good feedback that she is indeed doing something different. I then tell her to ‘Walk on, and keep making the pain’.

This is not easy, and is way more stressful than just sitting in the way which comes most easily. It may be even less easy in this saddle, which does not give the rider the length she needs from her seat bones to her knee. But elongating your thighs really does elongate the segment of the horse underneath them, and then he naturally and instinctively elongates his neck as well.

Alongside this use of the thigh muscles, the rider needs to bear down. To do this, you pull your stomach in, think of the muscles like a wall, and push your guts against that wall. You do this naturally when you cough, giggle, blow your nose, or clear your throat. You also do it naturally when you sweep and push the broom away from you. Your body instinctively knows that you have to connect the power of your pelvis into your upper body, and then into your shoulder girdle and arms.

When tennis players grunt, they are bearing down and bringing more power into their shot. The yells of martial artists have the same effect. But a very small percentage of riders realise that they have to bear down when they ride, and these are the 5% (or less) that we call ‘talented’. We use this word to say ‘She’s really good at it but we don’t know why.’ Bearing down is one of the key reasons why.

As our rider bears down, she needs to think of generating a ‘push’ that can push the horse’s head and neck further away from her. (In fact, I recommend that whenever a teacher tells you to ‘push’, you interpret her words to mean ‘push your guts against your skin’.) Our rider also needs to be sure that her hand delivers the message ‘You could reach if you would reach. I would not inhibit you’. I would like to know why she is riding in a pelham, and I fear that her problem might be that Paddy is too strong in a snaffle. If so, she needs major bearing-down therapy, for only this gives you the strength to anchor your body and ‘plug in’ to the horse’s back. Then you can give your hand forward, and discover the antidote to being towed along by the horse.

Our rider needs think of holding her hands as if she were pushing a baby buggy, and needs to be willing to let the reins slip through her fingers when the horse reaches. This must not happen to the extent that the rein becomes a loop; in this situation your aim is to maintain a light and even contact throughout. This requires a subtle and accurate response from you, and it also means that if the horse shortens his neck again, you widen your hands apart to take up the slack in the rein. Throughout this, you seek to discover that fine line between pulling and ‘washing lines’. You also need to pay attention to your thighs and the bearing down. If the horse scrunches his back and neck, you can bet that you will have lost the elongation of your thighs (and the pain that goes with it), and will need to set up your body all over again. And so it goes on, until you get better at doing it, you loose it less easily, and your horse becomes more willing to live and work in that elongated posture.

Good luck!