RWYM

ARTICLE 9

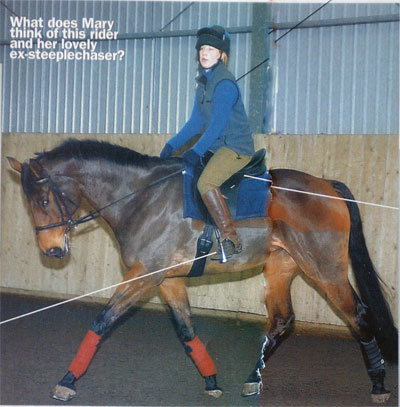

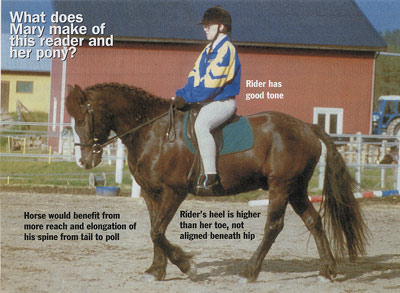

This sweet little horse is an Irish Draft X Conemmara gelding who is rising six. His present rider has owned him for two years, and feels that whilst he has improved from the ‘upside down’ horse that she bought, he does not yet stretch his topline in the way he ideally should. Neither does he lengthen his stride as she would like him too. She regards him as a calm and generous horse who ‘can be stubborn if he thinks he has been treated unfairly’. She does a bit of everything with him, and I’m sure that she loves him to bits.

This sweet little horse is an Irish Draft X Conemmara gelding who is rising six. His present rider has owned him for two years, and feels that whilst he has improved from the ‘upside down’ horse that she bought, he does not yet stretch his topline in the way he ideally should. Neither does he lengthen his stride as she would like him too. She regards him as a calm and generous horse who ‘can be stubborn if he thinks he has been treated unfairly’. She does a bit of everything with him, and I’m sure that she loves him to bits.

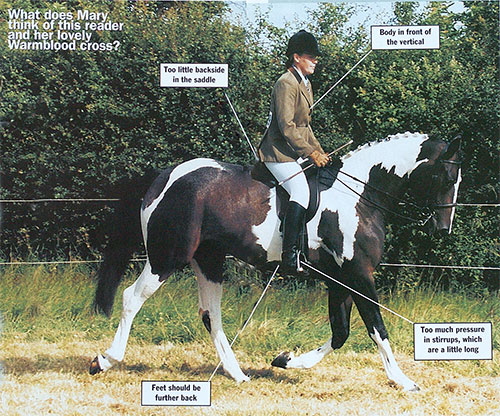

This photograph is taken from an angle which yields a very attractive picture, but which forces us to look carefully to get the information we need. My immediate responses are that this is a lovely little horse (and Conemmara crosses, are, in my experience, almost always good performers, perhaps because of the Iberian blood in their ancestry). As the horse’s owner states, his frame is too short, and he looks to me as if he is slightly above the bit and would really like to be more so. The shortness and hollowness of his frame are seen much more clearly in a second photograph she sent me, that was taken from the side. However, since I have talked a lot in these articles about how to lengthen the horse’s frame, I will focus here on steering.

The rider is making a turn, and we can see that she is looking to the inside in a very exaggerated way. As I look as the photo her inside hand jumps out at me: she looks to have a very strong contact with this rein, and I suspect that there is a lot of tension around her wrist and elbow. (When a part of the rider’s body ‘jumps out at you’ like this, you are seeing tense muscles.) We cannot see how strong the contact is on her outside rein, so we can only guess if this pull is unilateral or bilateral. Thus we cannot be sure how much the pull is indicative of the issues associated with the horse’s carriage (and an attempt to get his head down), or with the attempt to turn.

There is another important element here which is far less obvious. If you can find two biros, lie one along the axis of the horse’s nose, and one along the rider’s central axis, along the line of the buttons of her hacking jacket. You can then see that these lines are far from parallel – our rider is leaning in, so that her chin lies well to the inside of the horse’s mane. If you then lie one of the biros along the line of the top of the windows of the building in the background, you can see that her inside shoulder is lower than her outside shoulder. The tilt of her central axis could well be causing difficulties in turning, and by default, her inside hand is attempting to solve these problems by pulling on the rein.

It is a pity that this picture was not taken from straight ahead of the horse, because then we could more easily compare the axes of horse and rider, and also discern whether a line drawn down the horse’s nose would meet the ground between his front feet. I think that it would, that the axis of the horse’s nose is very close to vertical, and that he is not adding his own tilt into the equation.

Ideally, turning a horse is like pushing a wheelbarrow around a corner. You do not grab at the inside handle and pull; instead you push it along. The old masters often suggested that the reins should feel as if they are solid rods (like wheelbarrow handles), and this feeling – once you have learnt how to create it – makes steering the horse very easy. But if one or both of the ‘wheelbarrow handles’ can pull at you, or go soggy, or if the wheelbarrow seems to have a mind of it’s own, you are dealing with a very different scenario! This underlies one of the most devastating truths about riding: that the art of riding lies in making the horse easy to ride. Once you have climbed that great mountain, the problems you experience are far less.

I would like to know how clearly this rider can feel both of her seat bones. I suspect that her left (inside) one is heavier than her outside one. When all is well, the outside seatbone, the outside pelvis and the outside thigh are the primary initiators of the turn, but once that seat bone is ‘floating’ they cannot do their job. So the rider is left pulling on the inside rein.

To turn the horse without resorting to the inside hand, the rider has to get into ‘fencing lunge position’. A right handed fencing lunge positions her correctly for a turn to the right, and a left handed fencing lunge positions her correctly for a turn to the left.

It is this orientation of the pelvis and torso which naturally leads to your inside leg being ‘on the girth’ and your outside leg being behind it. However, being told about the correct position for your pelvis and torso is much more helpful than being told about the correct position for your legs. Then you are being led towards the core of the issue instead of merely being told about its symptom.

When the rider is loosing her outside seat bone, she has to try and find it, firstly by bringing her body onto the correct axis. She needs to keep glancing down to check that her chin is over the horse’s mane, and not to the inside. She also needs to think of searching for that seat bone further back than she might expect, and closer to the horse’s spine. Imagine sitting on a clock face, in which twelve o’clock points towards the horse’s head, and six o’clock towards his tail. In ‘fencing lunge position’, on the left rein your right(outside) seat bone is on four o’clock with the left (inside) one on ten to. On the right rein, your left (outside) seat bone is back on eight o’clock, with the right (inside) one on ten past.

As the rider who is struggling works around me on a circle, I often repeatedly ask ‘Can you feel your outside seatbone?’ and she has to answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. This keeps her brain on the job, and helps her to discover what happens when she gets it, and what happens when she looses it. If she is having a lot of trouble, I may check that she can easily feel both seat bones if she sits on a chair on her hands. If she can’t get both of them equal in this situation, then a visit to the chiropractor could save her hours (and even years) of drama.

I also often put the rider on a small circle in walk, and walk myself by the horse’s outside shoulder. Then I push the horse’s shoulders around the circle, thus giving the rider the feeling of the horse’s forehand turning correctly. I also poke the rider on the bony knobble which lies at the top of her outside thigh. This, along with the outside seat bone, initiates the turn, giving the rider the feeling that the horse turns from behind the saddle.

It should be quite possible to do this exercise with a friend, and you may both be surprised to realise the difference between a jack-knife – in which the horse’s shoulders fall out – and a correct turn, whose mechanism is akin to a turn on the haunches. In this, the horse’s forehand turns around his hind quarters, and the rider’s outside aids push him around, instead of her inside rein pulling him round.

OOur rider in the photograph needs to pin her outside seat bone in place, and of course, leaning to the inside will immediately lift it. Also, she does not need to turn her head so exaggeratedly in the direction she is turning to: since we can all see at least 180 degrees in our peripheral vision, you can see where you are going whilst looking straight on. And if she does turn her head, she can do so without turning her shoulders, since this twist will (as I explained last month) encourage you to twist your pelvis in the same direction. Once your inside shoulder and inside seat bone are back, you are in a position which is a complete reversal of the fencing lunge, and it does not have the desired effect on the horse. Furthermore, the twist will also encourage you to lean in, as the rider is doing here. Since that will lift your outside seat bone, you are now in dire trouble.

br /> iit – until she makes the necessary corrections within her torso. In learning and teaching, it makes all the difference in the world if you address the cause instead of the symptoms. So, I encourage this rider to pay attention to her central axis, to her outside seat bone, and to the idea of ‘fencing lunge position’. These seed ideas can germinate into the skill of turning the horse without recourse to the inside rein – and it’s so delightful when you no longer feel tempted to pull!